The fabled artists’ colony tends to feel like a figment of the past. It seems these incubators of innovation were teeming with the possibility of what we might make of art if we simply took a moment away to experiment with a few other inspired minds. A closer look at some of the most famous American artists’ colonies reveals that spirit may be more alive and well than we’d imagine. These places still carry traces of their storied pasts, and their legacies most certainly have informed the art which ensued. Perhaps surprisingly, there are a few colonies still running today, in one form or another. Read on to delve deeper into American art history, and hopefully mine a bit of inspiration along the way…

Byrdcliffe, New York

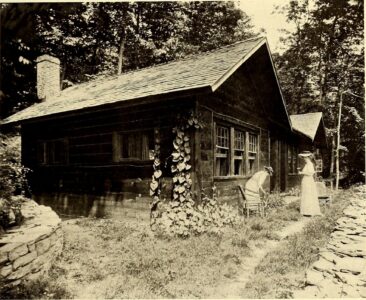

Byrdcliffe is nestled in the town of Woodstock, New York, an area with its own reputation for free-wheeling artistic expression. Although the Byrdcliffe artists’ colony came well before the infamous music and arts festival, putting down roots in 1903. It’s the product of husband-and-wife duo, Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead and Jane Byrd McCall. Ralph brought his British Arts and Crafts sensibility and Jane, an American drive for seeking out new modes of living in a vast area of natural beauty. The place sprung up on utopian ideals, taking shape as 30 or so timber buildings, complete with a library, an arts school, and an inn for visitors.

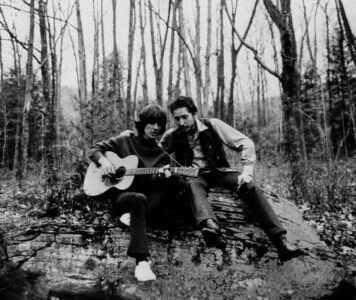

There was a focus on self-sufficiency at Byrdcliffe, where the community turned largely to furniture making as a means of filling the coffers. The dream of a self-funding community didn’t last all that long, but it did galvanise links between Byrdcliffe and the town of Woodstock. The two became inextricably intertwined, each adding to the other’s legacy as a hotbed for artists. It’s no coincidence that Bob Dylan settled in the town in the ‘60s, ushering in a local movement towards musical self-expression.

Byrdcliffe’s allure remains strong among artists, as it continues to host residencies, exhibitions, and educational programmes today. In fact, it’s now the oldest operating artists’ colony in America. Bob Dylan has been a key participant, as has painter Philip Guston and sculptor Eva Hesse. It has played host to a diverse range of creatives, with characters from comedian Chevy Chase to musical maestros The Band living and working there over the years. The pull of Byrdcliffe remains strong, and it’s certainly well worth stopping in to explore its historic environs for yourself.

Sedona, Arizona

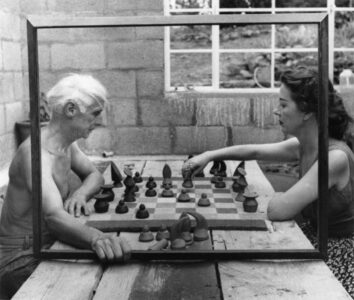

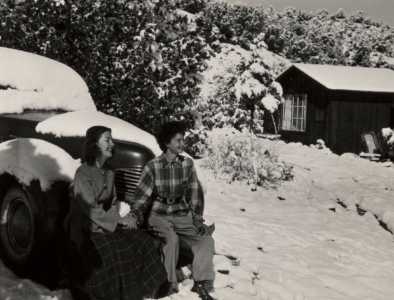

Surrealist couple Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning were drawn to Sedona for its otherworldly landscape in the ‘40s. They came by way of New York, building a home by hand in this disparate land peopled by about 500 ranchers, orchard workers, merchants, and Native Americans. There was a purity to the place which inspired the duo. It was as if the Surrealist visions in their minds’ eyes were brought to life and splashed all around them. The amorphous rock formations and technicoloured desert sunsets are the stuff of dreams, coaxing masterpieces out of both artists.

Max, hailing from Germany, drew a number of European intellectuals and artists to the area. The French Surrealist painter Yves Tanguy came to stay, as did a host of seminal photographers, including Henri Cartier-Bresson, Man Ray, and Lee Miller. Marcel Duchamp, the great luminary of the iconoclastic Dada art movement, even came to stay. This cross-pollination of American and European modes of creativity co-mingling in a place so separate from the salons of society produced a new spin on art. There was an intense connection with the land and a quality of existing within art itself, the landscape ageless yet ever-changing. The otherworldly setting was an ideal backdrop to whimsically composed scenes featuring artists as well as totems of the land – conduits for the spirit of Sedona.

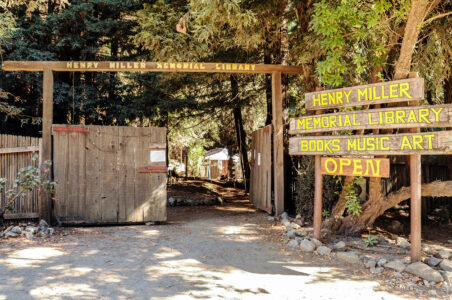

Big Sur, California

Big Sur sits teetering on the edge of the world, peering out at the Pacific from California’s cliff edge. It carries a largely literary legacy as something of an outpost for Beat poets, and the many permutations of creative which seemed to mill about them. It was the writer Henry Miller who got the gears turning and inspired others to follow in his footsteps from city to sea. He conjured visions of a place apart where inspiration grew on trees and a helping hand, though miles removed, never felt far away.

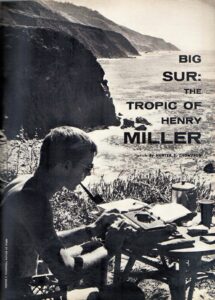

The title page of ‘Big Sur: The Tropic of Henry Miller’ by Hunter S. Thompson, published in Rogue magazine, October 1961

As a result, there was a steady stream of American icons who enjoyed at least a stint in Big Sur. Jack Kerouac spent time here in the ‘60s, spinning his novel, ‘Big Sur’ out of just ten days amongst the mist-muddled trees. In 1961 Hunter S. Thompson worked as a caretaker and security guard at Slates Hot Springs Resort. Esalen Institute then put roots down on that very spot and continues to offer alternative wellness programmes from that same location today. It was during this time that Hunter worked on ‘The Rum Diary’ and wrote his first feature story for men’s magazine Rogue, in which he took Big Sur’s reputation as an artists’ colony as his focus. He relayed tales of visitors rolling into town, asking where they might find these free-wheeling, riotous parties thrown by open-minded individuals. By this point, they were few and far between. Though, visit today and you’ll still find the spirit of a place apart from the modern world. There’s a divergent sort of creativity that hangs in the air, alongside a much slower, more contemplative rhythm of living. Perhaps this is thanks to the almost overwhelming natural beauty of the place, which gives inhabitants no choice but to pause in contemplation and turn to creative expression to exercise some of that awe.

Architect Mickey Muennig moved to Big Sur following a stay at Esalen Institute in 1971. He went on to become known as “the man who built Big Sur”. He’s behind a good deal of Post Ranch Inn, with its modern yet deeply earthy structures inspired by butterflies, among other creatures. Mickey’s style of organic architecture is both of and in the land. He sunk his homes down into the ground or perched them on stilts among the trees, building in native woods and stones. His architecture is very much a reflection of the spirit of the place – an environment where thinking outside the box couldn’t be more strongly encouraged.

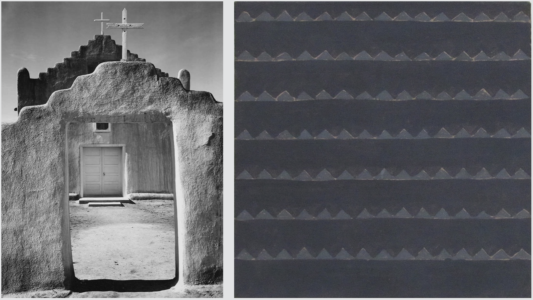

Taos, New Mexico

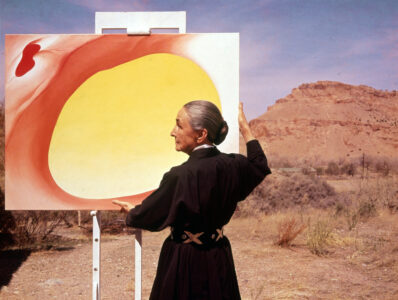

Georgia O’Keeffe with her ‘Pelvis Series, Red with Yellow’ in Taos; photographed by Tony Vacorro (1960)

Taos is a wild, windswept place in New Mexico with an almost mystical air about it. It has developed an artistic reputation thanks, chiefly, to Mabel Dodge Luhan. She was an heiress from Buffalo who held art salons in Manhattan as well as overseas in Florence before she settled in Taos in 1917. Her stature in the upper echelons of the art world drew attention to this sparse enclave of timeworn canyons and whistling winds, and eventually, the artists themselves followed. We have Mabel to thank for the conjured visions of Taos which flowed from greats like the painters Mark Rothko and Agnes Martin, as well as photographer Ansel Adams.

Georgia O’Keeffe is perhaps the figure most widely associated with Taos and its artistic history. She first visited Mabel there in 1929, and the lure of the place never left her. She returned often before properly relocating to Taos in 1949. Taos grabbed hold of her gaze and refused to let go as Georgia embarked on one of the most career-defining chapters of her artistic practice. She worked with her husband and fellow Taos transplant, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. Together they interrogated the forms and artifacts of this world apart. Georgia’s abstract approach to painting took on real life forms yet simultaneously became even more amorphous, melding with the soft yet stolid forms which surrounded her, bathed in that otherworldly light of this place she called “the faraway”.

Black Mountain College, North Carolina

Black Mountain College was an arts school perched in the hills of North Carolina, which many considered the American answer to Germany’s Bauhaus. After all, Walter Gropius as well as Josef and Anni Albers were key teachers at the school, having relocated from the Bauhaus as the Nazi threat loomed heavier and heavier over Europe. If we define an artists’ colony as a collaborative mixture of creatives removed to a region with an intense and inspiring sense of place, this little college certainly ticks the boxes.

Black Mountain College was founded by John Andrew Rice and Theodore Dreier in 1933 on a determination to foster a new sort of art through experimentation and self-expression. This disarticulation of the time’s typically structured, hierarchical art education system favoured an integrative approach to creativity. Making art was not relegated to classrooms during set periods; it flowed out across the landscape at all hours. Creativity was a state of being which interwove these burgeoning artists’ lives and work. Black Mountain College’s removal from reminders of a world beyond created an environment in which the rules were made up as they went along, if at all. There were no exams, grades, or tuitions to be paid here. There wasn’t even a defined timeline for graduation. It all unfurled fluidly and on the artist’s schedule.

Manning the ship were minds like Carl Jung and Albert Einstein, who both sat on the board of Black Mountain College. Now big names in the New York art scene flocked to the site, among them Cy Twombly, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, and Robert Rauschenberg. A spirit of collaboration led to the advent of the “Happening”: a multi-media spectacle of creativity and celebration of free thought. These painters helped to set the scene for dance performances choreographed by the likes of Merce Cunningham, set to the music of composer John Cage. The result was a moment of creative confluence which would inform the face of Modern art in America.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn