Sam Maloof was a humble, unassuming man who had a way with wood. He didn’t set out to be an artist, never mind a founding father of the American Craft Movement. In fact, he wasn’t even aware of any such movement as he carried on making furniture in his home workshop. Nonetheless, he’s lauded as one of the most prolific woodworkers in American history, and the first ever craftsman to be awarded a MacArthur ‘Genius Grant’. Maloof’s work, and perhaps more critically, his relationship to his craft, came to characterise twentieth century American woodworking as it took shape as a respected form of functional art.

Maloof lived in California all his life, from 1916 to 2009. He preferred the quiet life and remained resolute in the simplicity of his craft. From behind giant, owl-eyed rims, he remarked, “I don’t consider myself an artist; I never have. I am a furniture maker. I am a woodworker – and I think ‘woodworker’ is a very good word and I like the word. It’s an honest word.” Be that as it may, his creations are, in many circles, considered high art. A number of his rocking chairs took up residence in The White House, where they remain today. JFK set the precedent, introducing a rocking chair to the Oval Office as an antidote to the back pain stemming from a war injury in the Pacific. Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan followed suit, commanding the ship from their own personal rocking chairs made by Maloof. And so, honest beginnings in a quiet studio were a gateway to not only presidential praise, but the recognition of craft as much more than a service of utility.

Maloof’s work was nourished by his partnership with his wife, Alfreda – or ‘Freda’, as he called her. When the two first met in 1947, it was love at first sight. She was a painter, a ceramicist, and a weaver, all of which informed her savoir-faire as a creative partner to Maloof. He credits her for the ability to bring his visions to life as he did. “Freda was the heart and soul of what I do” he recalled. Their partnership in life was soon echoed in work. Necessity was very much the mother of invention here. Maloof began making things in earnest when he and Freda purchased a house and were left without enough money to buy furniture for it. The solution was simple: Sam would make furniture for Freda. He picked up discarded plywood and packing crates where he could, learning how to handle it as he went. Eventually, people took notice and began commissioning pieces, finally gracing him with the funds he needed to begin working with proper hardwoods like walnut (his favourite).

Larger projects came, funnelling his pieces into mid-century homes across California. He came to embody the spirit of West Coast pre-modernism. His work is characterised by a closeness to nature and a material-led approach, as well as a patient dedication to meticulous craftsmanship. “I’ve always felt that people should be surrounded by beautiful objects – objects that they really love”, Maloof explained. He viewed good design as a conduit for human connection. “It brings us into friendly contact daily.”

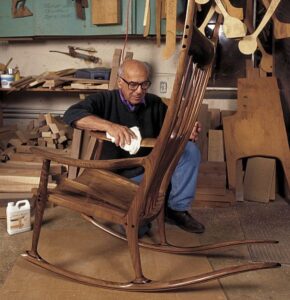

Maloof’s approach to craftsmanship was representative of his generation’s, many of whom (himself included) came to woodworking following their service in WWII. He was part of the vanguard forging a place for handmade furniture with character. He was self-taught and fiercely independent, taking pleasure in the pursuit of perfection through process and practice. Maloof considered himself an instrument for making beautiful objects – or perhaps more aptly, exposing and framing the innate beauty of natural materials. His furniture evolved as it was crafted. “I use the bandsaw as a pencil, really – as a design instrument”, Maloof explained – each work, a divination in walnut, ebony, or oak.

Maloof intentionally left the joints in his work on full display. He felt they were intrinsic to the beauty of each piece, as well as a nod to process and utility. He fit the pieces together with tact, like a puzzle, ensuring each creation was suited to viewing in the round. He figured a properly made piece shouldn’t have a bad side – even the underneath was polished to perfection, just in case.

Maloof is best remembered for his chairs, which rise and fall to the shape of the human body. The chair is perhaps the piece of furniture that exists within most intimate relationship with a person. Maloof’s are contoured to the human body and imbued with a sense of the maker’s hand. He coaxed beauty out of functionality, his rocking chairs being a prime example. Their rockers extend into elegantly elongated tails, which guard overly enthusiastic users from tumbling backwards. Maloof takes the opportunity to impart an artistic flourish while serving a purpose, bringing form and function into symbiosis.

Maloof worked with a sense of dynamism, creating furniture that holds its allure even in contemporary spaces. He made about 5,000 pieces over his career, many of which now enjoy homes in museums, from the Smithsonian to the Met. They were, however, made for friends and for enjoyment. Perhaps that’s what’s granted Maloof’s creations their staying power. His is furniture with soul.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn