Dada is an art movement that tends to incite spirited debate to this day. In fact, that was among its founders’ key objectives. This is a movement spearheaded by provocateurs with a message to spread – though, they often went about doing so in a cryptic, or even downright nonsensical manner. Love it or hate it, Dada started conversations. These were necessary discourses around society, art, and culture which retain their relevance to this day. Read on for a debrief on exactly how the work of these artistic enfants terribles played out…

The Dada movement took shape during the First World War, fuelled by an anti-establishment sensibility in objection to the horrors of war. It took root in Zurich, within the context of a neutral territory that became home to many artists and intellectuals seeking solace. In 1916, Dada found its home at the Cabaret Voltaire, where poets, performers, artists, and thinkers shared common ground and a container for creative expression. This provided the necessary footing for Dadaists to manifest their convictions, challenging the status quo with wit and verve. As the artist, Hans Arp wrote:

“Revolted by the butchery of the 1914 World War, we in Zurich devoted ourselves to the arts. While the guns rumbled in the distance, we sang, painted, made collages and wrote poems with all our might.”

The Zurich chapter of the Dada story begins with Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings. This husband-and-wife duo founded the Cabaret Voltaire, where their group convened in full force. They were German poets and performers, bringing an air of theatricality to the fore. Hugo Ball is remembered for his Cubist costumes, in one of which he delivered the first Dada manifesto, among other more abstract performances. Costume became a key element of the movement, helping to form its aesthetic and conveying the roots and references of Dada thought. The Romanian artist, Marcel Janco, for example, brought a primitive, almost ritualist feel into the fray with his mask designs. This would ripple out across other artists’ contributions to their cause, offering a common visual and cultural thread.

From a practical perspective, we can’t forget the role of Emmy Hennings. Although often overlooked, she was a key catalyst of the group, making their artistic expression possible through organising the many eccentric characters (which, one can imagine, would have been much like herding cats). She was the great conductor behind the Dada movement, though she also found occasion to perform in her own right, informing the ethos of the group. She was, in many ways, the spiritual core of Dada.

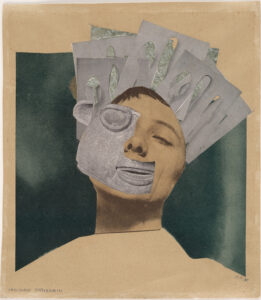

‘Indische Tänzerin: Aus einem ethnographischen Museum’ (‘Indian Dancer: From an Ethnographic Museum’) by Hannah Höch, 1930

From Zurich, Dada leapt across the border to Berlin in 1917. The group of artists who came to animate it took a particularly political approach in their work. Hannah Höch was one such contributor, shining a harsh light on Weimar society and mass culture. As the only woman involved with the Berlin Dadaists, she had decidedly more to say on the topic of gender roles than her counterparts. She created photomontage as a medium for doing so, critiquing established norms and urging viewers to question their assumptions concerning not only the place of female artists, but of women in society at large.

Marcel Duchamp is perhaps the best known of the Dada artists. He was among the group’s New York City adopters, who found resonance in the movement’s European roots and a clear place for them in American society. He was a sculptor and a true provocateur, converting everyday objects into what he called ‘readymades’. These were compositions of more than one object, presented so as to raise questions around the definition of art and its role in society. In doing so, he helped to invent conceptual art as we understand it today. His most famous artwork is a piece called ‘Fountain’, whereby he tampered ever so slightly with a urinal and presented it for public consideration. Its reception was, as one can imagine, fiery and fraught – a result which Marcel Duchamp would surely have considered a resounding success.

Another New York City Dadaist who might ring a bell is the photographer, Man Ray. He’s remembered for his pioneering ‘rayographs’, whereby he created what are essentially photos without the use of cameras. It’s important to note that the American model and war photographer, Lee Miller was integral to the invention of this new artistic medium. She tends to be forgotten in the story, though her collaboration was key. Man Ray often worked with bright young women who brought a certain lustre to his work. Characters of the Jazz age like Kiki de Montparnasse and Dora Maar shine brightly in his oeuvre, bringing a certain polish and panache. Ultimately, Man Ray played an integral role in bridging Dada and what would become Surrealism, creating space for many of the original movement’s principals and artistic methods to endure beyond its heyday.

When Dada reached Paris, it was André Breton who took up the mantle. The movement gained strength in a literary and theatrical respect, relying heavily upon the ideas behind the art. André Breton was a key thinker in the group and a major contributor to its creative processes. He was an ardent proponent of harnessing the subconscious for creativity’s sake, often using automatic writing as a means of mining the hidden trenches of the mind. He also looked to dreams as a source of inspiration, viewing them as another portal into something deeper, whether that be the subconscious, or even collective consciousness. This sort of thinking bears stark similarities to the bases of Surrealism, and eventually this better-known movement would subsume Dada. André Breton became Surrealism’s fearless leader, bringing with him many key principles of its predecessor.

Translation of sign: “For you to like something you must have seen and heard it for a long time bunch of idiots”

Dada is not an easily digestible art movement. It combined deep thought, ardent political beliefs, and probing cultural critique to present a new form of art. Dada produced art as interrogation and social instrument. It started constructive conversations around the definition and purpose of art which rage on today. From a creative perspective, many of its core tenets lived on in the form of Surrealism, rippling out across disciplines. Dada is a movement which, although difficult to put one’s finger on, is instrumental to many debates which were, and continue to be, worth having.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn