Film buffs may not know him by name, but they do have John Lautner to thank for some of the most captivating environments of 20th-century cinema. The works of this American architect were built around particular clients, conceived of as homes for families, bachelors, or artists. What transpired, however, was an opening up of these domestic locales. Film directors blew the doors open for all of us to momentarily experience life amidst these futuristic forms.

Lautner’s designs appear in iconic films from James Bond to The Big Lebowski. He drew the highly curatorial gaze of fashion designer-cum-film director, Tom Ford, The Schaffer Residence setting the scene for Ford’s directorial debut, A Single Man. His ultra-modern Chemosphere even appears in The Simpsons, demonstrating the degree to which his visual vernacular permeates culture across the board. His influence is also felt in iconic scenes like Uma Thurman and John Travolta’s Pulp Fiction twist, the set design for the’ 50s-inspired Jackrabbit Slim’s club being pulled directly from Lautner’s highly influential California coffee house architectural style.

Lautner grew up in northern Michigan, immersed in the great outdoors. The architectural seed was planted when, at 12 years old, he helped his father build a cabin on Lake Superior. He became immersed in this practical, hands-on approach to architecture. An understanding of the processes that went into creating a structure, as well as the ability to undertake them himself, were integral to his design approach. This served him well as an apprentice under Frank Lloyd Wright, who he helped design and physically construct Taliesin West. Lautner’s contributions ran the gambit, from designing certain elements to personally executing the stonework. He eventually splintered off to make his mark on the built landscape of California and ultimately, immortalise that uniquely modern character on-screen.

Chemosphere

The Chemosphere is anything but a conventional home. It looks more like a UFO that toppled into the treetops than any house. It sits teetering in the Hollywood Hills, just off Mulholland Drive. Its development began in 1960, when Lautner was approached by Leonard Malin. The young aerospace engineer had inherited a plot of land set at a 45-degree gradient and wondered if Lautner might be able to make something of it.

Lautner got to work, starting with a 9-metre tall, 1.5-metre-thick concrete pole. He devised an octagonal floorplan in the name of structural integrity. The format focuses the weight of the building on the single central point, transferring the load down the pole and into an underground concrete pedestal that spreads out to a 6-metre diameter. And so, it worked. Lautner had created what Encyclopaedia Britannica would call “the most modern home built in the world”.

Over the years, the Chemosphere has cropped up in films that draw on its futuristic otherworldliness, as well as its isolation. It’s the perfect home for the eccentric villain or an unlucky target, living isolated in this house reached only by funicular. It proved the ideal supporting character in Brian De Palma’s 1984 thriller-mystery, Body Double. This house sets the perfect tone for an eerie tale unfolding in a world apart, pitched high above the city in its own private canopy. Publishing maven and now resident of the Chemosphere, Benedikt Taschen flips the script. Of life from this landmark vantage point he says, “it’s like a wide-screen movie…always changing”.

Elrod House

Still from the Diamonds Are Forever film by Guy Hamilton set at John Lautner’s Elrod House

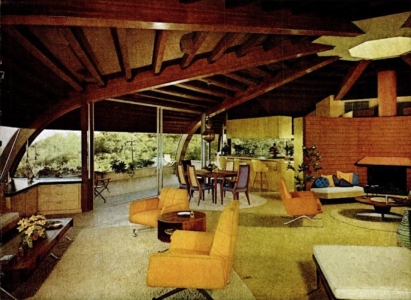

Lautner’s architectural inventions come in many forms. Some are angular, some round, some composed of biomorphic shapes, stacked one on top of the other as a ripple on the water. Elrod House combines all of these elements, echoing the multitudes of it surrounding landscape. It’s all about nature and open space, creating layers of vantagepoints that frame the world around it. Light and water are part of the very fabric of the architecture; they’re design materials more than they are elements. American architect, John Chase fittingly offers, “I think the difference between John Lautner’s work and that of other architects who are interested in this indoor-outdoor relationship is that Lautner buildings are more like landscapes in themselves”.

Still from the Diamonds Are Forever film by Guy Hamilton set in John Lautner’s Elrod House

The Palm Springs project was commissioned by interior designer, Arthur Elrod in 1968. It was an irresistible proposition for Lautner, working within this dramatic, rocky landscape. He embraced the obstacles, asking that the builders dig 3 metres deeper to expose more of the boulders on the site. He structurally and aesthetically integrated them into the house, creating a home that was truly part of its environment, inside and out.

Still from the Diamonds Are Forever film by Guy Hamilton set in John Lautner’s Elrod House

This hybrid home is a key setting in Guy Hamilton’s 1971 James Bond film, Diamonds are Forever. We see these rock formations abutting walls or, indeed, forming them entirely in a famous scene where 007 comes up against the beguiling assassins, Bambi and Thumper. It’s almost a challenge to focus on the action with so much unfolding in the environment as the camera pans across the sweeping forms and natural splendours of this hilltop hideaway.

Still from the Diamonds Are Forever film by Guy Hamilton set in John Lautner’s Elrod House

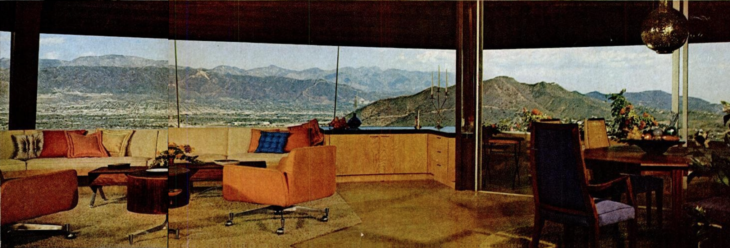

Sheats-Goldstein Residence

The Sheats-Goldstein Residence fits right into Lautner’s organic modern style, slotting in amidst shelves of sandstone overlooking Beverly Hills. He designed the house for a young artist, Helen Sheats, and her professor husband along with their three children. Interestingly, Lautner grew up in a similar family, with an artist for a mother and professor for a father, connecting with the couple over their shared vantage points. Bringing these into focus and establishing how they wished to live in their home, he built from the inside out, using existing natural formations to guide his design.

James Goldstein later bought the home, working alongside Lautner to ‘perfect’ it for his purposes. Lautner designed furniture that was imbedded in the structure of the building, like bench-style seating that creates a lounge effect looking out onto the pool. Their longitudinal, sand-coloured design perfectly echoes the natural environs, picking up on a common formal theme throughout the home. Fans of the Coen Brother’s 1998 classic, The Big Lebowski, will recognise these features in the eccentric (if psychopathic) Jackie Treehorn’s house. The Dude makes himself right at home, reclining belly-out on one of these orange leather-clad benches, serene as ever in this cavernous stronghold.

Still from The Big Lebowski film by The Coen Brothers, set in John Lautner’s Sheats-Goldstein Residence

Lautner’s designs don’t just tell the stories of fictional villains and eccentric homeowners. They capture the character of 20th-century Los Angeles, as it stepped into its legacy of modernity, expanding the purview of design. Lautner’s structural gymnastics inculcate the timeless, natural landscape into very futuristic built environments. In doing so, he created a unique brand of organic modernism and influenced the way that we live in relation to our larger environment. As John Chase asserts, Lautner’s designs “don’t box space in so much as they kind of cup space; they give you some degree of shelter while still allowing you to participate in the landscape”. Lautner’s contributions reframe life in modernity and set the scene for a future which can be both cinematically dramatic while hanging in perfect harmony with the extra-chronographic tides of nature.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn