When speaking of Mexican Modernism – or indeed, Modernism on a global scale – no conversation is complete without consideration of Luis Barragán. His name conjures visions of great, expansive courtyards, articulated by rectilinear forms set ablaze in bright bougainvillaea pink. This aesthetic vernacular is the culmination of a life spent dancing across the lines which define our built environments: light and shadow, interior and exterior, indigenous and imported.

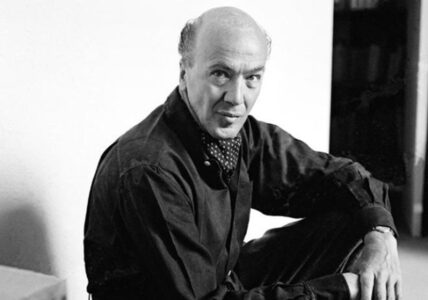

Barragán was born in 1902, living a privileged youth between Guadalajara and his family ranch outside the city. He studied engineering before setting off on his own extracurricular visual education. He travelled across Europe and the United States, taking in design fairs as well as the architectural works of maestros like Le Corbusier and Richard Neutra. Thoroughly edified, he returned to Guadalajara to embark on his own architectural projects. He stayed there for ten years before relocating to Mexico City, where he would remain until the end of his days, in 1988.

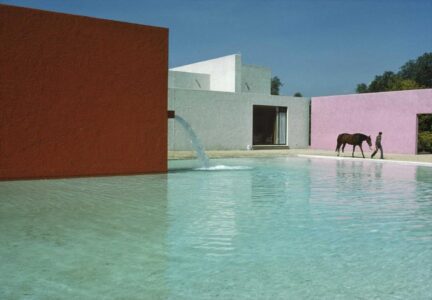

The lion’s share of Barragán’s creations is in Mexico City and its surrounding country. His body of work consists mostly of high-end homes both for people and horses. As he began to find his own expression of architecture, he drew upon far-reaching influences, including that of the obscure landscape architect, Ferdinand Bac. Exterior spaces came to occupy a central role in Barragán’s architecture, often taking up as much as half of the overall footprint of his built environments. He choreographed a delightful dance between interior and exterior, playing one off against the other. Often, the garden seems to exist less for outdoor use and more for enhancing the indoor atmosphere. The interior walls frame views of greenery, which bring life, light, and energy into the home.

This element of contrast was integral to the overall impact of Barragán’s works. Transitional points were not contained merely to the interior versus exterior. Many of the most important moments of revelation occurred indoors, taking form as transitory spaces. Barragán designed his houses so as to dispense a sort of protracted pleasure, measured and moderated as a visitor progresses through the architectural environment. He called it “architectural striptease”. Each transitional space is something of a palate cleanser, with constrained proportions and muted lighting to quiet the senses, preparing visitors for the next course. That may be a vast space of church-like proportions, buzzing with bright colours. It could be a room with a wall of windows, the life of the garden rushing forth against it. In any case, these transitions were very important to Barragán, like key changes in a song.

Colour is, to many, a calling card of Barragán’s. He was even known to request entirely pink meals at home. These brilliant hues were integral to the effect of his buildings, though they often served a larger purpose than simply bringing a “pop of colour”. Barragán’s blazing pinks and yellows were canvases for tricks of the light. From a young age, he was fascinated by the daily tug-of-war between light and shadow. As a schoolboy he would go out for long horseback rides, noticing, in his words, “the play of shadows on the walls, how the afternoon sun gradually got weaker—although it was still light—and how the look of things changed, angles got smaller and straight lines stood out even more”. Light was so important to Barragán that his architect friend recalled being disinvited to tea on various occasions because the light in the garden was not quite right the day.

Equally valuable to light was shadow, which Barragán prized as “a basic human need”. He denounced the all-glass structures of many Modernist contemporaries as “uninhabitable”. In contrast, his houses were exceedingly private, shielded behind high walls and shrunken street-facing windows. Nowhere is this more evident than in the architect’s own Mexico City home, in the artistic Miguel Hidalgo neighbourhood. The place was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2004, immortalising the architect’s home and studio of forty years.

Casa Luis Barragán was built in 1948, harnessing the power of bright colours, geometric forms, and open expanse – all brought to life by light. Each element is in communion with the space and sky which surrounds it, with architectural features like the high, coloured walls of the rooftop purpose-built to frame the azure airwaves above. The building is something of a church of Mexican Modernism. It draws upon Barragán’s Catholic sensibilities in order to brush up against the beauty of what lies beyond our human experience here within Earth’s built environments.

Casa Luis Barragán can be considered an intermediary between ourselves and the divine. As Alberto Ruy-Sánchez Lacy puts it, “To explore the world of Luis Barragán is to establish a dialogue with the horizon. For it is a horizon that speaks: it poses questions and it responds with forms, making the boundaries of our own world more liveable”. The home of the man, himself is a place where our own human nature, manifest in the physiological necessity of shelter, meets the heavens – the open sky – the ineffable other. And it is so bold as to interact with it, framing it, influencing its cool colouration by comparison with hot, bougainvillaea pink – it establishes an interface. We, uncouth, warm, needing – and it, perfect, cool, and indifferent.

If the work of Barragán was rooted in any existing architectural form, it’s the traditional Mexican village. He raises towering exterior walls which give way to passageways, plazas, and fountains. He fuses this with sequestered Spanish influences, fostering a symbiotic relationship between the indigenous and the colonial. Barragán, himself noted that his work is inherently autobiographical – though, it’s also arguably political, articulating its messages regarding his country’s nascent democracy through a symbolic fusion of influences. His architecture champions “forms of coexistence and solidarity”, which encourage communities to “revise and adapt to the conditions of modern life”, as the Mexican poet Octavio Paz phrases it. So, these aesthetic icons of colour, geometry, and light converge as a manifesto. They communicate the life story and convictions of a man, equal parts conservative and eccentric (Barragán exists today in the form of a diamond, forged from his ashes in the name of conceptual art – though, that’s an entirely separate story for another time). The man and the work are embodiments of dichotomies, each brought together to form an alchemical whole which far outshines the sum of its parts.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn