There’s a certain honesty to Japanese design which is perpetually pleasing. There’s a respect for materials often married with a sublime sense of simplicity. This reductive approach seeks to expose the idiosyncrasies of an object, rather than to hide them. In Japan, the natural and the manmade go hand in hand, with designers emulating the forms they find in the wild and harnessing organic materials throughout their creations. The result is a certain style of design which is very much in and of the place. Modern Japanese architecture, furniture, and design objects join to form a harmonious sort of hum, creating a cohesive soundtrack to daily life.

These deeply embedded principles of Japanese design have long been on Tom’s radar. He, too, designs with simplicity in mind and an exacting eye on materials. Join us for a trip through some the most famous works of modern Japanese design which continue to inspire Tom and the contemporary creative world at large…

Japanese Architecture

The Yoyogi National Stadium has become a true emblem of modern Japanese architecture. It was completed in 1964 to host the Tokyo Olympics, though continues to welcome architecture afficionados to this day. Its draping and pooling form speaks to the architect Kenzō Tange’s inclination to design buildings in reaction to their context. The form rises from the landscape of one of Tokyo’s largest parks, taking shape in smooth curves which emanate from a central spine. At the time of its completion, the stadium’s suspension roof was the largest of its kind, globally. Tange took inspiration from European architects like Le Corbusier and Eero Saarinen, adapting elements of their style to suit the setting. He references the Japanese pagoda, though treats it in thoroughly Modernist terms. We’re left with a confluence not only of east and west, but of past and present.

Tadao Ando completed his now infamous Church of Light in 1989, though it manages to feel strikingly contemporary to this day. It sits in a tranquil neighbourhood just outside Osaka, emanating an air of solidity and quiet power. It’s a small structure – no bigger than a typical house – though its blocky, concrete form carries a certain gravitas. Step inside and you’ll be ensconced in sleek, stony walls, conjuring a cool and contemplative atmosphere. The church’s defining feature, though, is the minimalist cross that’s been cut from the concrete. It stretches from wall to wall and ceiling to floor, with natural light rushing in through the slender slats. Ando often enfolds Zen philosophies into his architecture, and certainly did in this case. He frames duality through his manipulation of form, pitting light and dark against one another. Similarly, he captures the tension between solidity and emptiness through this starkly beautiful design. The result is a space which encourages consideration of the opposing yet inter-reliant qualities of faith, bringing the ephemeral and the embodied into a harmonious sort of communion.

Kengo Kuma is a key figure in Japanese architecture, creating spaces which, although modern in form, are designed to speak to our humanity. His Oribe teahouse is an expression of his belief that buildings should feel warm and natural, extending a gracious welcome to all who enter. It was designed in 2005 to honour the daimyo tea master Furuta Oribe, who used rustic, organically shaped bowls in his ceremonies. Kuma reinterprets these qualities using corrugated plastic boards, which can be disassembled and carted off to different destinations. The structure itself has an ephemeral quality, resembling a cloud which may well float away if left untethered. It creates a perfectly peaceful environment for the traditional tea ceremony, while breathing new life into an ancient art.

Japanese Furniture

Sōri Yanagi’s 1954 ‘Butterfly’ stool could go by various names. Many, of course, view its form as reminiscent of the wings of a butterfly fluttering open. Some detect the shape of a Shinto shrine’s gateway. Others view it as a nod to the traditional samurai helmet. However you see it, it’s a stunning piece of modern design which has stood the test of time. In its making, Yanagi was undoubtedly influenced by Charlotte Perriand, for whom he translated on her trip through Japan. He also cites a visit with Charles and Ray Eames as something of a watershed moment in his practice as a product designer. He adapted their bentwood techniques into something entirely his own, coaxing a strikingly sculptural seat from simple plywood.

Isamu Kenmochi’s ‘Kashiwado’ chair was designed in 1961, harnessing the raw beauty of Japanese cedar. It’s a celebration of the natural material, which is arranged in blocks to showcase the woodgrain in all its glory. There’s a chopping block quality to the piece, its sheer front face melting into the form of a seat. The design takes its name from a famous sumo wrestler by the name of Kashiwado Tsuyoshi, embodying the fighter’s sturdy, robust characteristics. It’s slightly rustic in effect, with a simple and unadorned quality which echoes the Modernist ‘less is more’ mentality while grounding the style in a distinctly Japanese heritage.

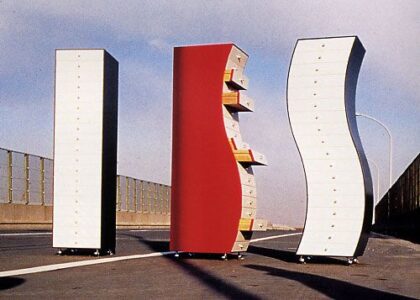

‘Drawer in an Irregular Form – Sides 1, 2, and 3’ cabinets (from right to left) by Shiro Kuramata (1970)

Shiro Kuramata’s 1970 ‘Drawer in an Irregular Form’ series is quite literally the stuff of dreams. The designer was inspired by the visions which danced behind his own sleepy eyes, adapting them into the now iconic ‘Side 1’ cabinet before extending the range. The piece snakes upward in an S-curve, imparting a sense of dynamism and vitality. The cabinet plays into the work of Ettore Sottsass as well. Kuramata was delighted by his whimsical approach to design, eventually moving to Milan, himself and joining Sottsass’s famous Memphis Group. The trio of cabinets ultimately fits together as graduated puzzle pieces, very much like Kuramata’s diverse yet complementary sources of creative inspiration.

Japanese Design Objects

Isamu Noguchi’s ‘Akari’ light sculptures are among the most enthusiastically embraced examples of Japanese design. Their simplicity and organic character help to establish their timeless allure. Noguchi harnessed the intrinsic beauty of Japanese paper, which has long been some of the finest on the global market. The washi paper enfolds a patiently constructed network of bamboo ribs, each strip laid one by one to produce a sculptural whole. As Noguchi put it, “the harshness of electricity is thus transformed through the magic of paper back to the light of our origin – the sun – so that its warmth may continue to fill our rooms at night”. Well, what’s more timeless than the sun? It’s no wonder these icons of Modernism have remained coveted emblems of Japanese design since their conception in 1951 through to contemporary times. With more than 100 iterations to choose from, the intrigue of their weightless luminosity is truly endless.

Japanese ceramics are among the finest in the world. They’re buttressed by a certain set of philosophies which lend added meaning to each piece. In the Shibui pottery tradition, for example, there is an embracing of imperfection and a desire to reveal beauty as opposed to control it. Tom has been collecting Japanese ceramics for some time now and is particularly drawn to the work of Akiko Hirai. Her style is modern and unique, while simultaneously rooted in a deep sense of tradition. She stands on the shoulders of Shibui masters, drawing from a deep history of craft. Many of her particularly distinctive pieces evolve from a process of layering. She prefers to relinquish an element of control, allowing the clay to dictate the direction the form will take. She then surrenders her creation to the kiln, where nature can take its course, unveiling the stunning idiosyncrasies which make her work so special. Her ceramics are a true celebration of chance and imperfection – that which no hand could recreate even if it wished.

The Japanese art of Kintsugi, like Shibui pottery, is driven by a deep appreciation of chance imperfections. A vessel is broken only to come back together more beautifully than before. The pieces are reunited through a process of golden joinery, where the cracks are mended to create luminous rivulets of gold trickling across the form.

Tom has adapted this approach into the Cloud ‘Kintsugi’ console table, merging his own distinctive style of furniture design with the Japanese tradition. The top is made in steel, which is heated and then hammered so that flakes of metal fall away like shale to produce our unique ‘Moon’ finish. The surface is then cut into pieces before its reunited using molten gold. The top sits on long, slender legs, each of which are hammered to create a craggy texture with an elegantly tapered form.

Tom often looks for inspiration in his frequent travels as well as in the art he encounters along the way. Just last year he visited Japan for an immersive trip through some of our world’s most staggering sights. This cultural exchange of ideas travelling between east and west is no new phenomenon, though it does feel especially resonant today as we look for new ways to foster a global mindset and richer, more complex forms of creativity. And that’s exactly where modern Japanese design and contemporary British furniture meet: in shared ideas which embolden us to reimagine the forms which tradition can take.

Tom with ceramics sourced from Yuzemi on his Capricorn console + velvet wallpaper design for Fromental

Text by Annabel Colterjohn