Many think of Black Mountain College as the American answer to the Bauhaus. What came out of the schools were, in many ways, aesthetically distinct from one another, though the sensibilities that animated these pedagogical spaces where closely interlinked. There was even a great deal of cross-over in the respect to the characters involved. These were experimental schools with a decidedly artistic focus that would change the course of art history.

Black Mountain College was founded in 1933 by John Andrew Rice and Theodore Dreier, among others. The school sat perched in the mountains of North Carolina, where it enjoyed 24 years of experimental, grassroots artistic expression. There was a sense of bucking the status quo, largely led by Rice, who was intent on fracturing the stringently structured, hierarchical education system which ruled the day. This was a college built around philosopher, John Dewey’s principles of education, which focused on art as the central element of a holistic liberal arts education. He firmly believed in the power of making art as a means of imparting skills of observation, judgement, and action. These, to Rice, were the three key pillars of an adaptable, far-reaching education which could be applied to all areas of life, professional and otherwise.

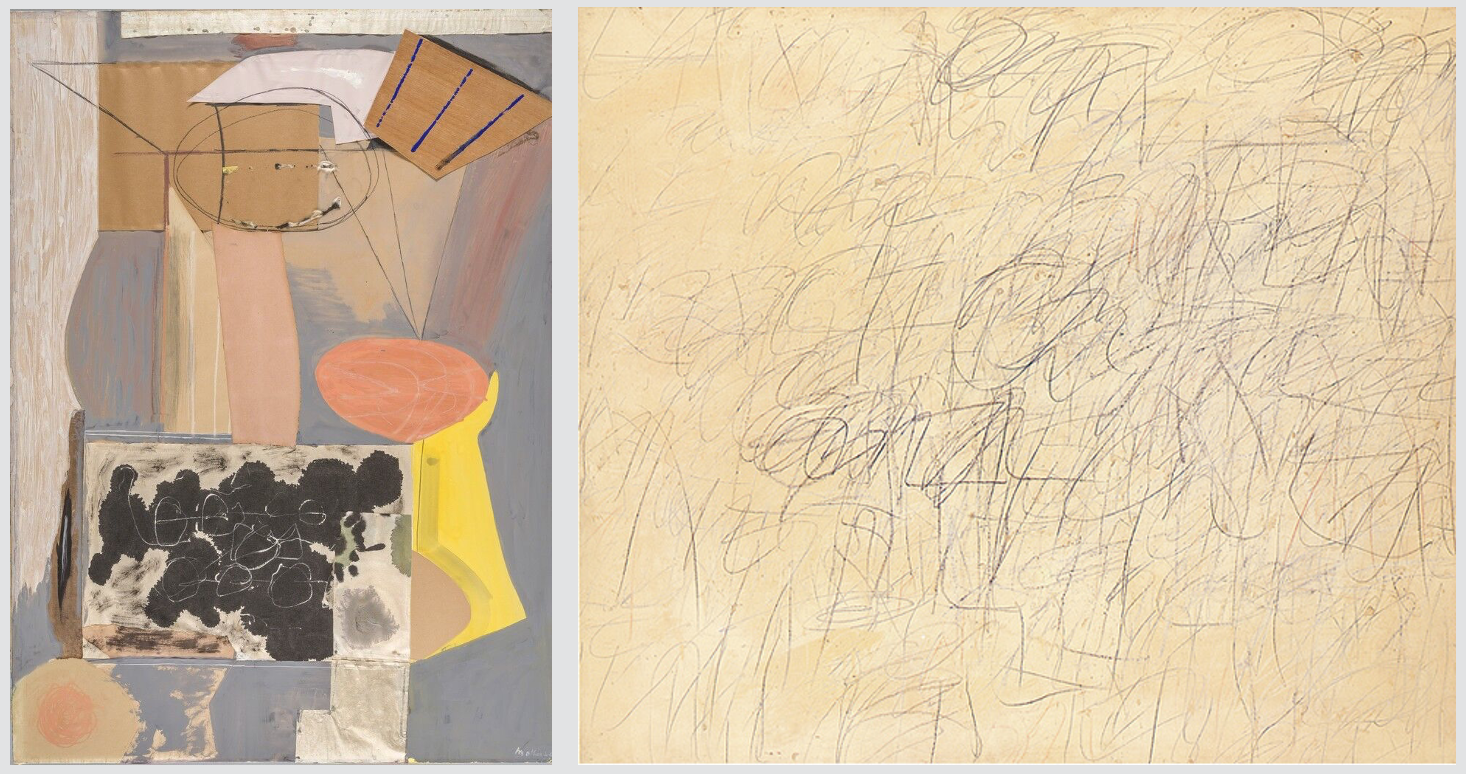

The physical isolation of Black Mountain College created ideological space to explore new ideas and experiment with their implementation. This incubator of thought had some pretty excellent minds on its side, bringing together ideas from various places and intellectual backgrounds. Even Albert Einstein and Carl Jung were on the board of advisors. It was an environment that became a creative laboratory for modern artistic talents like painters, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, and Cy Twombly. Their work emerged alongside the sinuous sculptures of Ruth Asawa and geodesic architectural inventions of Buckminster Fuller.

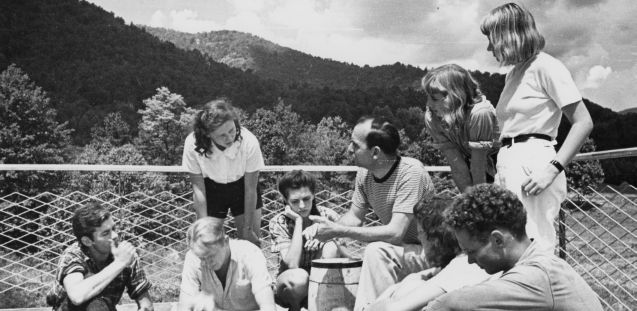

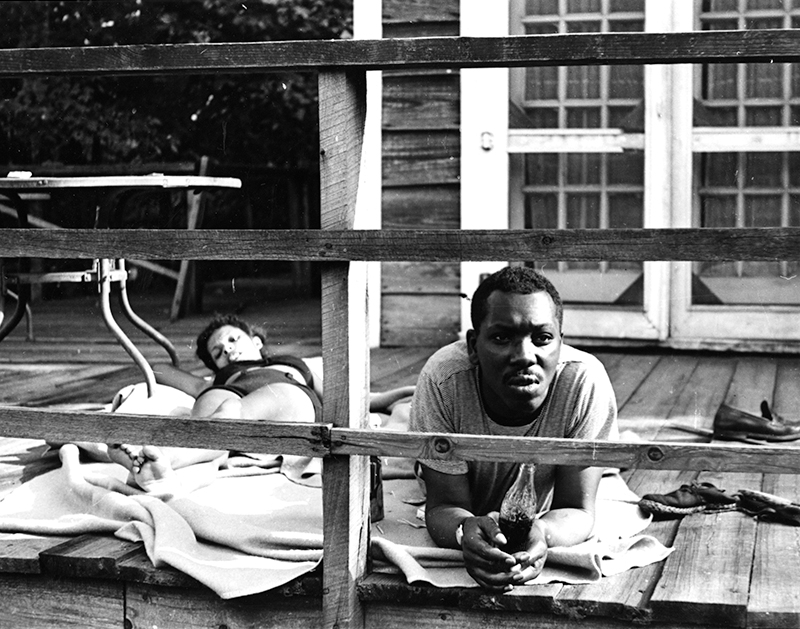

The environment was anything but ordinary. The usual educational fixtures – grades, exams, and even tuition – were done away with. There was no timeline for graduation either; students simply concluded their time at Black Mountain College when they felt they had got what they wanted out of it. Pupils and teachers lived together, connecting on a personal level far beyond any classroom. They were brought closer by parties and shared meals, as well as work on the college’s farm and maintaining this place that had come to be their shared home.

This artistic community was a melting pot of ideas, where creative experimentation was enthusiastically encouraged. Collaboration was a core principle at the college as well, fostering a give-and-take between painters, poets, and dancers, alike. Performance took on a central role in this recasting of the artistic hierarchy, with multi-disciplinary pieces taking place regularly. ‘Theatre Piece No. 1’, for many, marked the birth of ‘Happenings’ and performance art, where shows often went on with no rehearsal at all, unfolding intuitively as artists wove their crafts together in real-time. Composer, John Cage was struck by the idea for a performance at lunch one day in the summer of 1952. By dinner, he had dancer, Merce Cunningham on-side, as well as poet, Charles Olson. The visual artist, Robert Rauschenberg dressed the stage with his work, completing this confluence of media which spurred on a collective reimagining of what art could be in the modern era.

Teacher, Josef Albers explained, “We do not always create art, but rather experiments. It’s not our intention to fill museums; we are gathering experience.”. Josef and Anni Albers came to Black Mountain College after fleeing the Bauhaus under the looming threat of the Nazis. Here they not only found employment but a fresh, American strain of modern artistic evolution. Nearly a dozen Bauhaus transplants followed in their footprints, ending up at Black Mountain College, either as teachers or students. The opening of this new American creative frontier dovetailed neatly with the closing of the Bauhaus, beckoning to European intellectuals and artists who sought refuge across the Atlantic. Walter Gropius was one such character, bringing his progressive principles and architectural prowess to the mountains of North Carolina.

Black Mountain College was the embodiment of a burgeoning modern sensibility – not just in the arena of the arts but in life at large. The school carried inflections of the seeds of social upheaval taking root across the globe, banding together to propose a new educational, artistic, and social order by example. With one world war emblazoned in the collective sensibility and another on the horizon, as well as The Great Depression and the first pangs of McCarthyism making themselves felt, there was certainly a place for alternative modes of existence in society. As Gropius noted, “Every thinking man felt the necessity for an intellectual change of front”.

The unorthodox, if obliquely socialist, bent of the college drew attention from the FBI, who ominously characterised it as “a very unusual type of school”. There was an aversion to cultural movements outside of the norm and a concern for what sort of ripple effect may ensue – but, in short, those within the status quo thought these Appalachian acolytes were plain weird. The painter, Dorothea Rockburne delighted in confirming this suspicion upon the FBI’s visits, reminiscing, “Of course the students at Black Mountain put on an act for them. One of the favourite student tricks was to not have shoes on in the middle of winter and crunch out a cigarette butt with their bare feet. It confirmed their worst opinions, and we did not answer any of their questions.”. The FBI took note of this curious culture of creation, mentioning, “A student may do nothing all day and in the middle of the night may decide he wants to paint or write, which he does, and he may call on his teachers at this time for guidance. They advised that everything is left to the desires of the individual.”.

Black Mountain College leaves behind a legacy of freedom of expression, experimentation, and collaboration. There was an understanding of art both as social practice and as a panacean teacher. Those at Black Mountain College created art as a means of understanding the world, and in doing so, they redefined the boundaries of its role within society. The school’s short run was just a flash in the pan of art history, but we can be grateful that it burned brightly enough to cast its pioneering light through generations to come.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn