Wendell Castle was a daydreamer. He absconded from his childhood classroom into conjured visions of himself as a race car driver. Later, he tumbled into imaginary explorations of vast, amorphous forms, which would become the foundation of his creative practice. His work oscillated between sculpture and furniture, before emerging as something entirely its own: art furniture. It was through this creative innovation that Castle harnessed the race car driver in his mind, pushing ever onwards and taking the risky routes to unlock new artistic territory.

Castle grew up in Kansas in the 1930s, forging his way through school with undiagnosed dyslexia and leaning into these imagined domains as well as his love of drawing. He recalls, “If there was a spelling bee and you’re going to choose up some team, I would not be chosen. So, at some point I think I learned that I had to choose myself – and in art that can work”. It wasn’t until he reached university that his talent caught the eye of those beyond the realm of his imagination. His art teacher, Doctor Simone encouraged Castle to leave the school and study at a university with “a real art program”. Castle did exactly that. He settled on pursuing Industrial Design at the University of Kansas so as to appease both his parents and his creative drive. He ultimately began working as a sculptor, though he found it to be a rather crowded market with numerous young artists toiling away to have their work seen and appreciated.

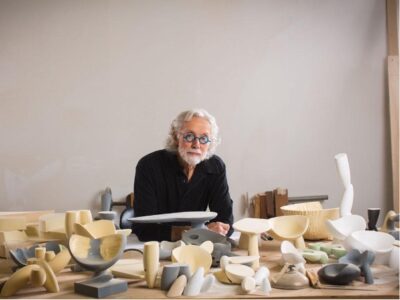

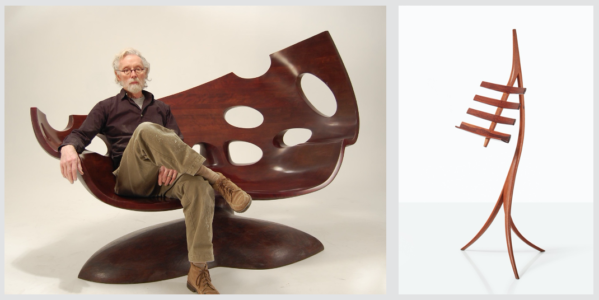

Wendell Castle in one of his signature art furniture pieces (left) + Wendell Castle’s Music Rack, 1964 (right)

Castle’s ‘inside gap’ (to stick with racing parlance) appeared at the intersection of the aesthetic and the functional. “I saw an opportunity,” he recalled. “I could see that to make it as a sculptor was a tough road. There were an awful lot of people doing that. Then I saw this other thing that nobody was doing – virtually nobody.” So, he took a plunge into new territory, exhibiting his ‘Music Rack’ at the 1964 Milan Triennial. To say the piece was a success would be an understatement. It took the art world by storm, cementing his trajectory as the Father of the Art Furniture Movement.

With a bit of wind beneath his wings, Castle picked up and moved to New York in the 1960s. He began exhibiting his creations in galleries, attracting attention from collectors and critics. This was the perfect arena for him to emerge as a disruptive force in the art world. He focused his practice on advancing what is artistically possible, dismantling the formal hierarchy that delineated between ‘art’ and otherwise. Castle’s creations were novel in that what they are at their core is art that happens to be functional. He went as far as to note, “I think of my work as anti-design”. He wasn’t so concerned with utility and efficiency; his furniture is often virtually immoveable – and most of its formal elements are not included for the sake of function, but rather to achieve a certain aesthetic vision. He wanted his work to be thought of as sculpture – collected, exhibited, and considered in artistic terms.

Castle’s ‘Executive Desk’ of 1973 is a stunning example of his emphatically sculptural approach to making furniture. The form of this walnut desk is remarkably fluid; even the drawers aren’t rectilinear. They take on organic, graduated shapes, fanning and curving out of the desk, perpetuating a sense of movement in the piece. It’s a strikingly dynamic design, emerging as an asymmetrical, cantilevered piece of sculpture that doubles as a worktop.

The scale and complexity of the forms that populated Castle’s fantastical daydreams called for his own unique techniques. He was drawn to the process of stacked lamination, which he first picked up through a craft magazine when he was a teenager. He was fascinated by a blueprint for a duck decoy, formed by piling pieces of roughly cut wood that are later honed to produce the desired form. He didn’t have the tools to execute the project at the time, but the idea never left his mind.

Decades later, Castle resurrected the stacked lamination technique, applying it to furniture production. It gave him greater flexibility to create exactly what he envisioned without being compositionally led by the shape or grain of the wood in its whole, organic state. His focus was on form and, as such, the approach worked well for him. He relinquished some of the idiosyncrasies of the material in favour of the volume of the complete object. It’s interesting that Castle’s pieces take on such biomorphic, organic forms, given they’re manufactured in accordance with his own imagination, as opposed to informed by the raw state of the wood. First, he deconstructs the natural form, only to rebuild it in his own, hyper-organic vision.

At a certain point, some of Castle’s visions became too complex to be executed by the hand alone. He introduced computer design and robotics to this stacked lamination process, which further expanded the possibilities for his work. Though, he always took over the final stages of each piece, maintaining his connection to the work and a certain presence of the human hand. He began to experiment with material as well, diversifying his oeuvre beyond wood to include metal, plastic, and concrete. At times, he even introduced light as a material, punctuating his pieces with luminescent orbs.

Castle was an unconventional thinker, who’s mind spun unusual forms that his hands made into entirely new objects. He spent his life expanding what was creatively possible and carving out space for these new artistic tides to flow. He worked under the banner of his ’10 Adopted Rules of Thumb’, the final one reading, “If you hit the bullseye every time the target is too near”. We see evidence of this blazing commitment to push ever onwards in each curve and corner or his work. His daydreams were fuel for this creative innovation, shifting the target further and further into the distance. One’s imagination and capacity for success is unlimited in daydreams; there are no boundaries or opportunities to falter. But there comes a time that one must step out from the safety of his own internal machinations to take his shot, hit or miss. In doing so, Castle most likely left a smattering of inexact executions, but he also created the space to push the envelope of what’s possible – and that’s exactly what he’ll be remembered for.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn