Fine art and design play exceptionally well together, with an ongoing interchange of ideas, aesthetic styles, and techniques continuously infusing new life into creative processes. Artistic thinking is not bound by form or function. The borders are permeable and some of history’s greatest creative movements flow through them. Cubism tumbles from painting into plasterwork; De Stijl leaps off the canvas to form furniture; and the celebration of materiality strides from sculpture to support contemporary tabletops.

Engaged in the artistic tides that flow between mediums and through time, Tom Faulkner embraces the inspiration they bring to his furniture design practice. There is a fluid give-and-take between his designs and the great movements in art. The same is true of past creators such as painter, Jean Metzinger and plasterer, Valentine Schlegel. Their final products are formally distinct from one another, yet their shared creative approach sends common motifs trickling through both creators’ work, blurring the lines between fine art and design.

Jean Metzinger’s Le Goûter (1911)

Jean Metzinger’s Futuristic style often collided with Cubism and Le Goûter is an excellent example of this intersection of fractured forms and the almost crepuscular softening of line in suggestion of movement. The sitter raises a spoonful while obliquely addressing the viewer, allowing us to take stock of her features as a collision of angles. She exudes both a sharpness and a softness simultaneously, as some her features – for example, her nose – jut and recoil at acute angles, and others – say, the sinuous musculature of her right arm – curve languidly from one point to another.

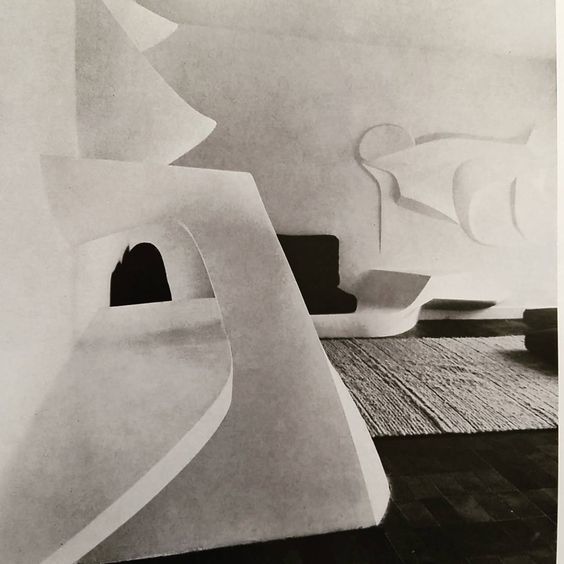

Plasterwork by Valentine Schlegel, photographed by Suzanne Fournier-Schlegel

This tension between harshness of line and fluidity of form flows through French plasterer, Valentine Schlegel’s work as well. Much of her best-known projects are centred around the hearth. She frames the cavernous fireplace incompletely, allowing for interplay between it and the greater environment. She melds her plasterwork into the surrounding walls, rather than neatly entrapping the fireplace within discrete boundaries. There is a certain mercuriality to her forms, which both define and obscure boundaries. This classically Cubist interplay between seemingly oppositional qualities, between splicing and re-integrating, is a core element of both the artist and the craftswoman’s oeuvre.

Where Metzinger and Schlegel were occupied with the porous, malleable quality of boundaries, Piet Mondrian sought to build a clear-cut framework for artistic creation through the De Stijl style of art. Aptly named, the Dutch phrase translates simply to “The Style”. Mondrian codified his beliefs around aesthetics and spirituality as an attempt to express reality at its core. The school stripped away representation in favour of pure abstraction as a means of cutting through to the immutable basis of all existence. To that end, works of De Stijl were composed with vertical and horizontal lines, the spaces between them rendered in stark white, grey, or primary colours. Gerrit Rietveld followed suit, translating the school’s thinking into solid furniture. Tom Faulkner picks up on this process of re-iteration in his furniture design, casting the tenets of De Stijl in more modern terms.

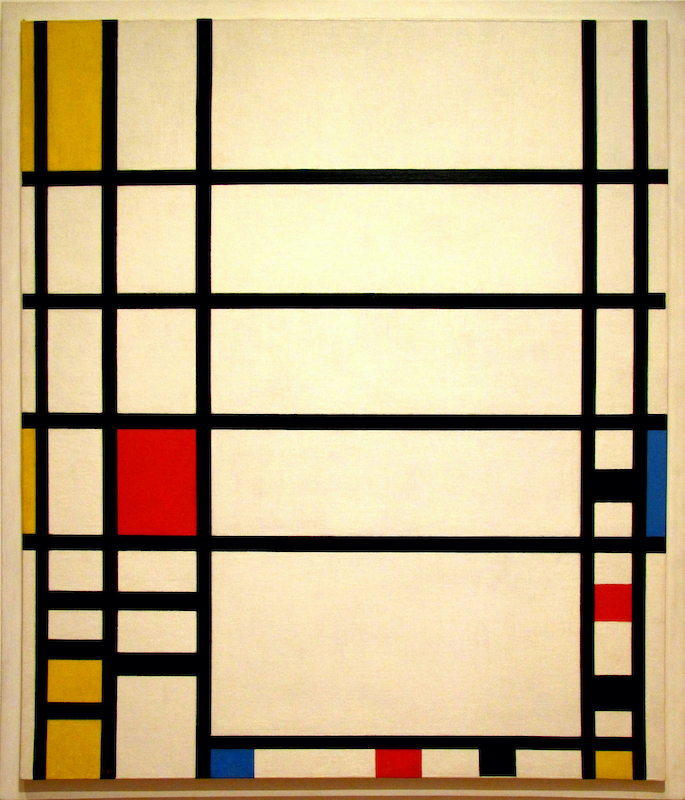

Piet Mondrian’s Trafalgar Square (1939)

Piet Mondrian’s embodiment of De Stijl comes in the form of an almost clinical delineation between spaces and a palate of strictly prescribed colours. There is a formality to his work, which belies a measured and absolute system of thinking. So tightly did he abide by his artistic manifesto that he ceremoniously turned his back on lifelong friend and De Stijl acolyte, Theo van Doesburg simply for introducing diagonal lines to his own artworks. God forbid.

Gerrit Rietveld’s Red Blue Chair (1917)

It’s difficult to say whether Mondrian would approve of his artistic style’s later adaptations within the design arena. In any case, he was and remains a greatly influential force of inspiration to those with a bent towards strong geometric lines and boldly simplistic bursts of colour. Gerrit Rietveld designed his famous Red/Blue Chair in the same aesthetic vein. Characterised by linearity, a considered use of colour, and an almost compartmentalisation of open space, the chair is a solid manifestation of the De Stijl sensibility. Though, here the designer has freed those qualities from the canvas, adapting them to suit a more utilitarian, domestic role.

Tom Faulkner’s Albany Mirror

Tom Faulkner’s Albany Mirror embraces the visual vocabulary of De Stijl, paring it back for a more modern, clean final product. Though forged in rigid materials, the piece is in constant flux as it reflects elements of its environment and those who inhabit it. The Albany Mirror welcomes mutability and fluidity where they would not have been found in Mondrian’s expressions of De Stijl. The world at large is not locked out of the piece but, rather, reverberates from it, breathing new life into a once placid, static style of art.

At times, attention to materiality takes on a key role in this interplay between life, art, and design. The painting, the chair, and the mirror all add something vastly different to the story of De Stijl as a result of their physical make-ups. This integral role of the medium comes to the fore in Alberto Giacometti’s sculptural works as well as in Tom Faulkner’s latest design, The Cloud Coffee Table.

Alberto Giacometti’s Homme qui Marche (1960)

In Giacometti’s Homme qui Marche, the artist embraces the crudity of bronze as a material, approaching this quality as an asset to be artfully featured, rather than an unruly force to be tamed into capitulation as shining, manicured forms. The same is true in the case of Tom Faulkner’s Cloud Coffee Table. Both works stand upon spindly legs of bronze, which exude a clear sense of the hand as it gives form to the material through traditional techniques. The Cloud Coffee Table takes shape through classical blacksmithing techniques, which meld brute bronze into a refined support for the elegant Calacatta Oro tabletop. Similarly, Giacometti casts his raw bronze into fine art, leaving it to ossify as the spidery limbs of a man lurching into motion.

Tom Faulkner’s Cloud Coffee Table in Calacatta Oro Black Patina

Detail of Tom Faulkner’s Cloud Coffee Table in Calacatta Oro Black Patina

A clear sense of craft reverberates from both pieces, which each borrow from the techniques of tradesmen past to culminate in objects which hold court as elevated forms of art and design. In this case, the material dictates the terms of engagement, as the maker must employ a forceful hand in transmuting brash bronze into more delicate incarnations, while retaining a sense of its ruggedness and utilitarian gravitas.

Although distinct in their purposes, paintings, plasterwork, sculptures, and furniture are united in the artful, considered processes of those who create them. Aesthetic ingenuity, modes of thought, and celebrations of materiality are only a few of the threads woven throughout creative disciplines. They coalesce at the points where fine art and design meet. These are places where free-thinking is given boundless room to expand in all its iterations.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn