Good design is difficult to pin down – but we know it when we see it. In the UK, we’re lucky enough to be surrounded by the work of countless design greats, elevating our everyday and inspiring future creations. From architecture, to furniture, to graphics, our world is composed of design. These creative expressions are the brushstrokes that make up our days, weaving beauty into the fabric of our lives. We have many to thank for this enrichment through functional beauty, but there are a few British icons of design that warrant special mention…

Terrence Conran

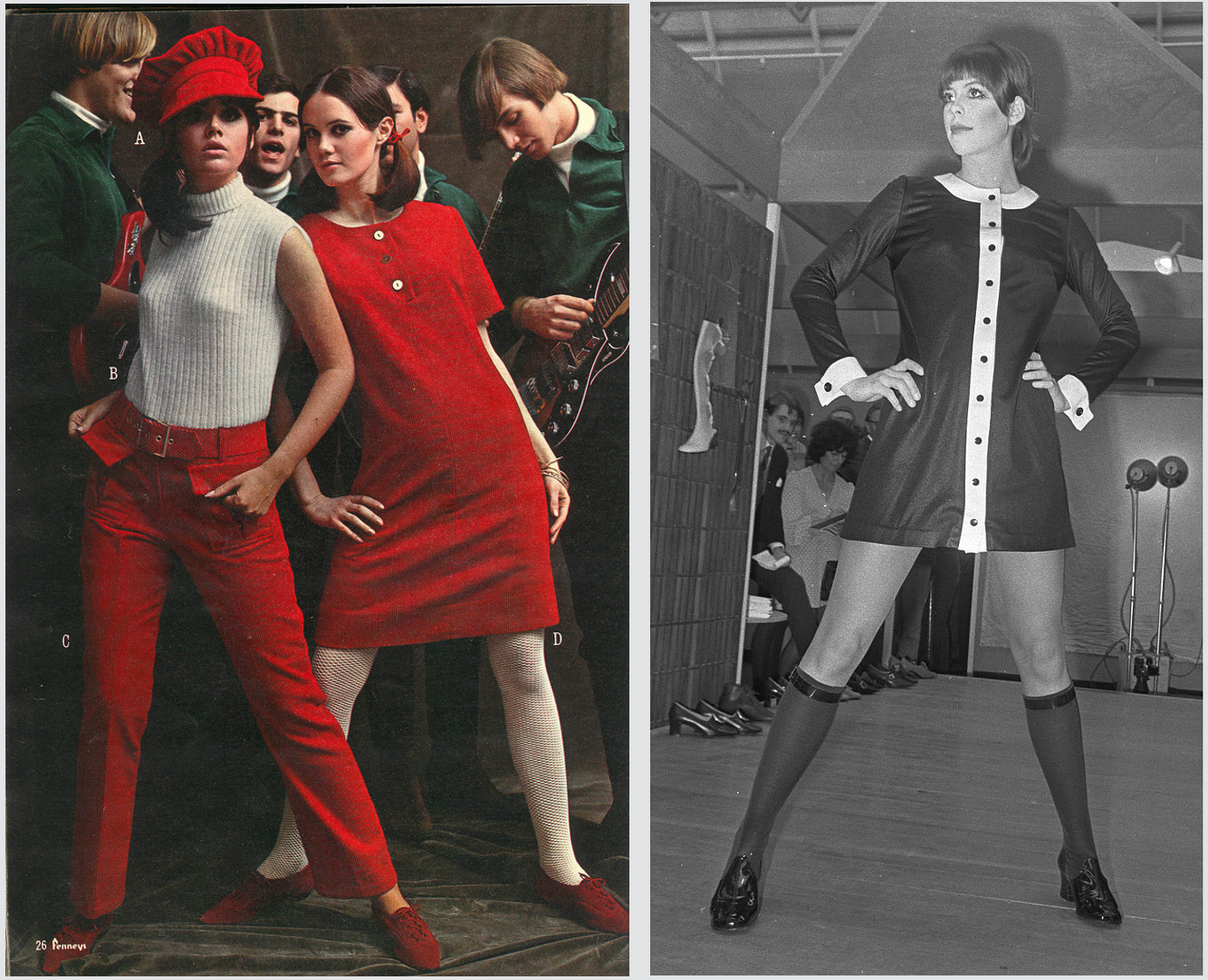

Terrence Conran leaves a legacy of bringing good design to the people. Over the course of his colourful career, he founded the Design Museum, Habitat, The Conran Shop, a few restaurants, and even a publishing subsidiary to produce the lion’s share of the over fifty books that he wrote. Under the banner of his and Fred Roche’s architectural consultancy, he converted the Michelin Building at London’s Brompton Cross into the restaurant and oyster bar that it is today. He gave the famous Bluebird Garage a similar treatment, designing its contemporary incarnation as a restaurant.

Left: Interior of Claude Bosi Oyster Bar in London’s Michelin Building, converted by Terence Conran | Terence Conran’s ‘Hector Bibendum Table Lamp’

All along the way, he designed his own furniture and fostered countless other creators. In line with his Bauhaus-inflected philosophy, he made considered design accessible through cost-effective solutions like flat-packing furniture for home assembly. To Conran, “design is there to improve your life”, and that’s true for everyone.

Mary Quant

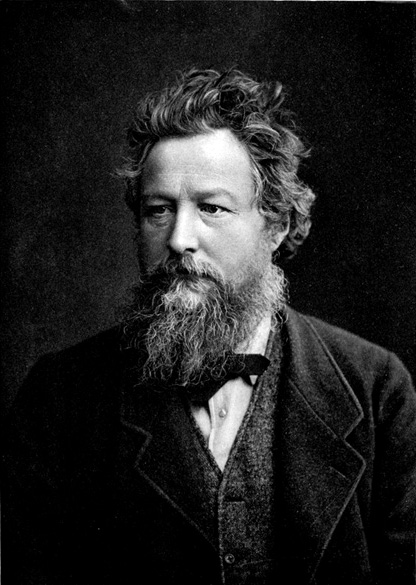

Mary Quant is not just a figurehead but an instrumental character in the Mod and youth fashion movements of 1960’s London. Her fun-loving, free-wheeling design ethos took form in the miniskirt, a sartorial staple of the era. She felt the diminutive style was liberating, and even practical, giving women the ability to run for the bus, among more courageous pursuits. She named her ‘invention’ after her favourite car, the Mini, and would even go on to design a special edition ‘Mini Quant’ model, of which thousands were released internationally.

Mary Quant found inspiration in her customers, the bright, energetic kids of Kings Road. She notes, “they are curiously feminine, but their femininity lies in their attitude rather than in their appearance…She enjoys being noticed, but wittily. She is lively – positive – opinionated.” These are the women she designed for – and indeed, empowered to raise the colourful banner of a new cultural dawn characterised by liberation and progressive optimism.

As the cultural arbiter, Ernestine Carter remarked, “It is given to a fortunate few to be born at the right time, in the right place, with the right talents. In recent fashion there are three: Chanel, Dior, and Mary Quant.”. Her influence is even immortalised in Peter Blake’s updated Beatles cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, an accolade which speaks for itself.

Norman Foster

Norman Foster is, not just in Britain but globally, one of the most prolific architects of our time. His contributions to design range from icons like London’s affectionately named ‘Gherkin’ of 2004, to his symbolic 1999 reconstruction of Berlin’s Reichstag following Germany’s reunification. In his early days he worked alongside Su and Richard Rogers as well as his wife, Wendy Foster. He later branched off to start his own studio, now Foster + Partners, which is the largest architectural practice in the UK at a staff of 1,500.

Foster’s signature style began to take shape through his interest in the idea of technologically advanced “sheds” – essentially simple structures that were enrobed in lightweight exoskeletons. His 1978 Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts is an excellent example of this approach to design. He’s become renowned for his innovative approaches to design, producing buildings that are at once futuristic and resplendent with a sense of rhythm and movement sliding along swooping swaths of metal and vast fields of glass.

Foster is also a veteran of the Royal Air Force and a keen pilot, which no doubt gave him an edge designing numerous airports from Beijing to Mexico City. He even went as far as designing a shining ring to house Apple’s headquarters in California, aptly nicknamed ‘the spaceship’. Foster’s contributions to design are the stuff of legends, and it’s in that pioneering spirit that he established the Norman Foster Foundation. He built the organisation with an eye to nurturing fresh design talent and blazing new trails in technological innovation. We can safely say he’s made an indelible mark on the built environments we inhabit, enriching our daily interactions with our world through design.

William Morris

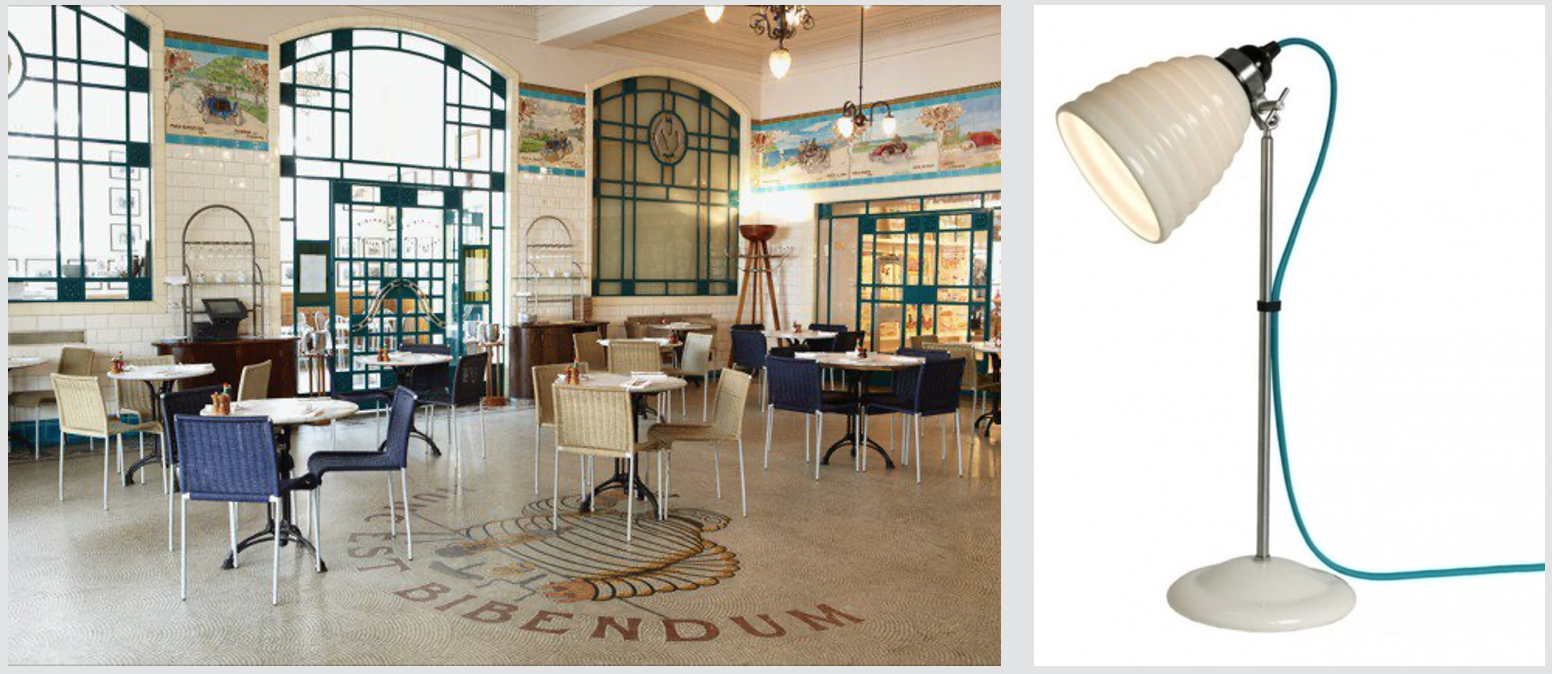

William Morris was a man of many talents. His contributions took form across poetry, art, social reform, and design. His close connections with Pre-Raphaelite artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones informed his creative and philosophical sensibilities. He had a fascination with Medievalism, stemming from his time at Oxford, which permeated his ideas on social and cultural systems. Morris also put a great deal of stock in aesthetic expression, with views largely inspired by the works of John Ruskin.

Ultimately, Morris used the arts to demonstrate what he considered the ideal manner of living and relating within society. His work was characterised by a pronounced return to craft and the central role of the hand in creating beauty. His ideas appealed to the individual as master of his own kingdom, as opposed to cog in the industrial machine. There was a considerable measure of romanticism in his contributions, driven by ardent Socialist values and a passionate belief in the power of aesthetic beauty to transform our world for the better. This quotidian beauty was, to Morris, not only a tool for enrichment, but also a barometer of the spiritual and moral health of society at large.

Morris’s textile, furniture, and stained-glass designs, replete with intricate, often vibrantly coloured natural motifs, were manifestations of his ideas. They fit into artfully designed homes like Morris’s own 1860 ‘Red House’, built in the intentional, aesthetically led spirit of the Arts and Crafts Movement. His ethos has been widely influential on key creative movements like the Bauhaus, as well as social initiatives like Environmentalism, leaving behind a legacy of considerate creation and useful beauty built to last.

Peter Saville

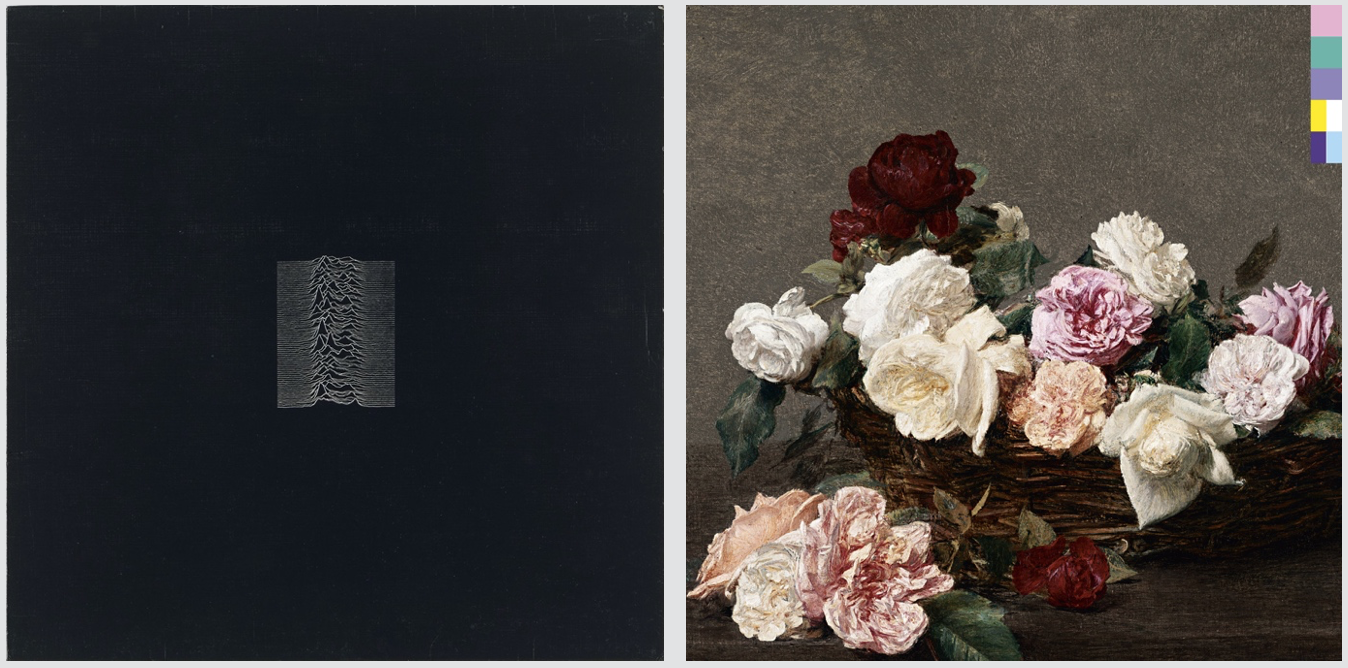

Peter Saville is best known for his iconic record sleeves, dating back to the 1970’s. You don’t have to be a fan of Joy Division to recognise Saville’s hypnotic lines on their 1979 ‘Unknown Pleasures’ album cover. He designed for label, Factory Records, which he cofounded in 1978, giving him a great deal of artistic autonomy. He attributes the success of his designs, in no small part, to this creative freedom, which stemmed not only from his hand in the company but also from album art as a medium. “Nobody didn’t buy a record because they didn’t like the cover”, he remarks in an interview with the FT. “There is no other form of graphic production that matters less. So, I could always do what I wanted.”

Left: Peter Saville’s album art for Joy Division’s 1979 ‘Unknown Pleasures’ | Right: Peter Saville’s album art for New Order’s 1983 ‘Power, Corruption & Lies’

Saville goes on to credit graphic design as delivering “the privilege of cultural awareness disseminated through consumerism”. He brought, for example, the work of 19th century French painter, Henri Fantin-Latour to the cultural fore in his design for New Age’s 1983 album, ‘Power, Corruption & Lies’. His oeuvre calls upon artistic movements of the past, yet sits outside any single one of them. It exists, instead, in this slipstream of a cultural continuum, riding cyclical resurgences and interspersing aesthetic elements of diverse provenance. The result is a body of work that speaks to the intricately constructed zeitgeist of an era, one that is a patchwork of references floating outside of time or cultural categorisation.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn