Biomorphism is not corralled into any one creative arena. It finds expression across artistic ateliers, from painters’ studios to architectural offices, to furniture workshops. These forms are derivative of natural phenomena. They melt and undulate in a visually organic manner, reaching their final manifestation as delightfully familiar, uniquely captivating shapes with soft, rounded edges and an air of continuity.

It’s interesting to consider why so many of us from such varied personal backgrounds find a common appreciation for biomorphic forms. Much of it can arguably be boiled down to the ubiquitously evocative role of nature in our lives. Natural forms constitute something of a common language. We understand it and, for the most part, appreciate it. So, biomorphism offers an excellent tool for tapping into nature as an emotional, sometimes even spiritual, font of creativity. Many artists working with biomorphic forms look to nature as an embodiment of truth in the purist sense of the word. They recognise the natural world as the heart of the human experience and, indeed, all existence. These artists turn to biomorphism as a means of sublimating the influence of human constructs so as to access these fundamental truths.

Works of biomorphism often conjure in their viewer his or her own recollections of natural phenomena. For example, a Catalonian viewer of Dalí’s artworks may recognise in them the almost molten formations of Monserrat, whereas another onlooker may flash back to the dripped sandcastles of his or her youth. Biomorphism speaks to many, though it harbours endless possibilities for personal translation. In his 1929 painting, Enigma of My Desire, My Mother, My Mother, My Mother, Dalí projects the human construct of language onto the biomorphic mass emerging from the ground. In each alcove, a keen eye will spot “ma mere’, or “my mother” in English. In doing so, he uses nature as a source of inspiration and a basis unto which he projects his own personal experiences. This process does not end with Dalí, as viewers are, in turn, drawn to cast their own interpretations upon the work, sustaining a tradition of extrapolation from nature.

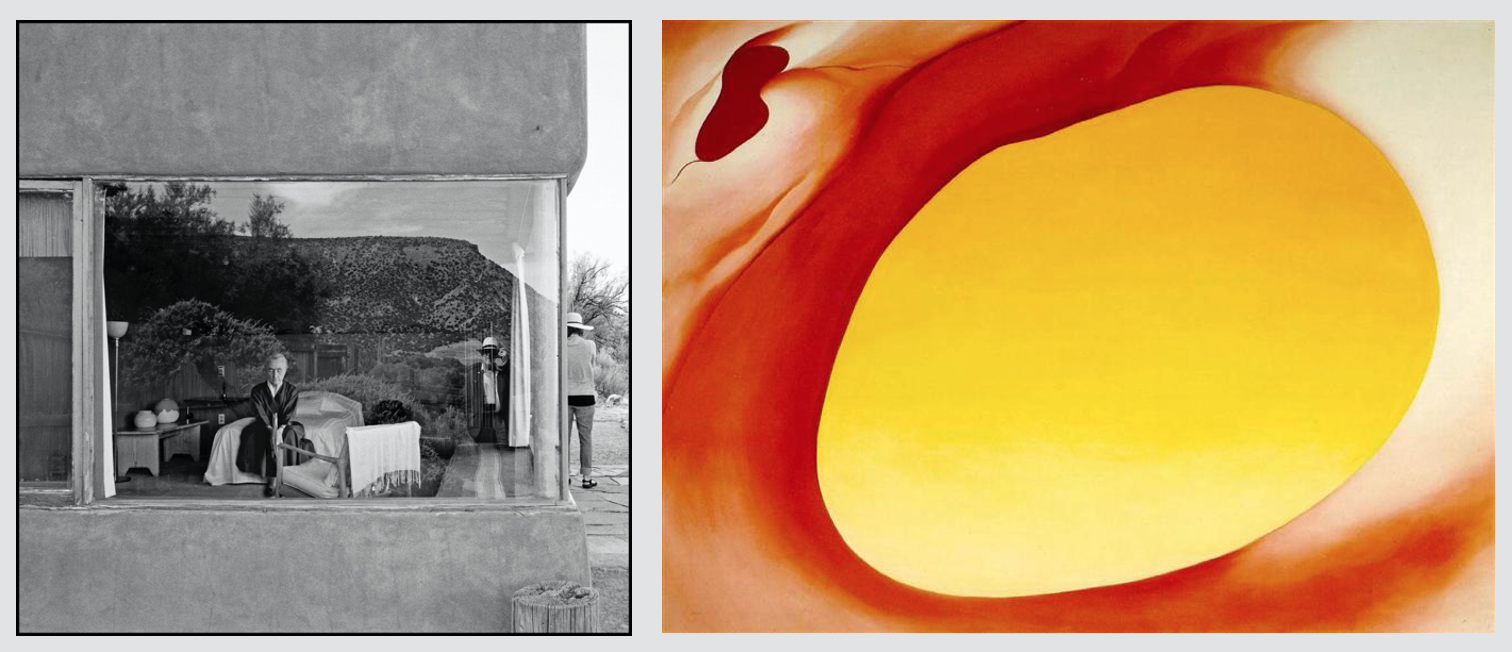

Left: Georgia O’Keeffe at her Abiquiu House, photographed by Ben Ledbetter;

Right: Georgia O’Keeffe’s Pelvis Series – Red with Yellow (1945)

Georgia O’Keeffe was famously enthralled with nature. She made a home for herself in the “Wild West”, settling in Abiquiu, New Mexico. She took up residence in a simple building with great swathes of windows so that she could immerse herself in the natural landscapes that fed her creativity. In her paintings, O’Keeffe fixated on flowers, mountain ranges, and even bones, as in her 1945 work, Pelvis Series – Red with Yellow. She represented these natural forms in an abstract manner, frequently through biomorphism. Though, the true natural bases of her works were often stranger than fiction. The majesty of these inspirational ephemera was too vast to capture and chronicle. Instead, she offers something of an ode to them, remarking, “[m]y painting is what I have to give back to the world for what the world gives to me”. She does not seek to replicate the things which she finds, which would essentially be an exercise in re-gifting. Rather, she aims to proclaim her appreciation for them, casting that in brushstrokes and bricks that stand the test of time.

T. H. Robsjohn-Gibbings’s Mesa table, credit: Yale University Art Gallery

The American Southwest found veneration once again in the works of British furniture designer, Terence Harold Robsjohn-Gibbings. He grew up in England, though settled in New York in the 1930s, turning his hand to a decidedly American visual vernacular that drew upon the country’s natural landscapes. The Mesa table, which Robsjohn-Gibbings designed in 1951, is a prime example of this approach. There is an air of materiality that links the table to nature through the use of richly striated wood. This was then melded into forms that drew upon the natural, time-worn wonders of the American landscape in a bid to capture and honour its essence. The result is a piece of furniture which borrows the visual composition of the flat-topped “mesa” mountains of the American Southwest, casting it in wooden biomorphic plates, which stack to form the topography of a Modern classic.

Jean Arp’s Impish Fruit (1943)

Jean Arp adopted a similar practice in his sculptural works, superimposing biomorphically shaped wooden cut-outs to produce artworks reminiscent of the natural world. Arp’s 1943 sculpture, Impish Fruit demonstrates this practice, prefiguring Robsjohn-Gibbings’s Mesa table. Here biomorphic forms take centre stage, comprising the entirety of the artwork, rather than playing contributing roles as in Dalí’s painting. So, the figurative ode to nature surpasses a simple nod and becomes the “point” of the artwork as a whole.

Mexican architect, Javier Senosiain joins these artists in the custom of borrowing from organic forms as a celebration of nature. He does so through creating conditions to live in closer harmony with the natural world. His 1984 design of Casa Orgánica, located in Naucalpan, Mexico, is reminiscent of an underwater cave, the walls morphing into tables and light fixtures before opening up into amorphous portholes to the outside world. The concrete pours over itself, calcifying into slick slabs to compose a vision of nature adapted to suit comfortable human habitation. The result is a home which, though it mimics nature, does not replicate it. Instead, Senosiain recasts the essence of organic wonders so as to encourage closer commune between man and the natural world.

Left: Tom Faulkner’s Lily Cocktail Table, Short with Green Murano Glass;

Right: Tom Faulkner’s Lily Mirror in Florentine Gold

Tom Faulkner was inspired by the unique outline of lily pads in his design of the Lily collection. The shape is adapted into coloured Murano glass to top the Lily Cocktail Table. The material’s irregular divots send light rippling through the translucent slab, conveying the effect of sunlight glistening off the slick surface of a lily pad. Tom has also cast this shape as the Lily Mirror, with an ambling silhouette rooted in the organic form of a lily pad. Lily is a fine example of the beauty which can come from looking to nature for creative inspiration without an intention of reproducing the original but rather, creating something new in its spirit.

In their endeavours to connect with nature as the hypostasis of life, artists who find expression through biomorphism are limited to producing man-made objects removed from that very foundation. As René Magritte famously reminds us, “Ceçi n’est pas une pipe”. The same is true of Georgia O’Keeffe’s painted bones, Jean Arp’s sculpted fruits, or Javier Senosiain’s built caves. They may take nature as their grounding but in beginning any form of work they relinquish ties to the purity of that work’s natural starting point. So, biomorphic art is to be taken as an homage, a conversation starter, a statement. It cannot capture the nectar of its basis as human creativity is an imperfect vehicle in conveying these perfect truths. Though, as an emotionally charged, shared language, biomorphism offers new avenues for connecting with the natural wonder that surrounds and sustains us all.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn