When we consider the concept of materiality in art, the mind focuses in on the medium itself, naturally. Take, for example, Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall. It’s defining feature, for many, is its emphatically metallic outer shell. At first glance, the building stands enveloped in an undulating cloak of sheet metal, which unfurls just enough to welcome visitors. On the other hand, we have the contrived materiality of Fernand Léger’s futuristic paintings. It shows up again in the modern creations of furniture designer, Tom Faulkner. This one swooping, metallic strain of materiality flows across media and through time to influence various creators. It starts in an industrial, mechanistic setting, translating into a symbol of modern potential and an opportune medium for creating the forms of a beautifully functional world. Materiality does not have to be determined solely by the physical medium itself. Rather, it can be distinguished and perpetuated by the manipulation of form, the use of colour, and the development of movement, as demonstrated from every corner of the creative arena.

Fernand Léger’s La Partie de Cartes

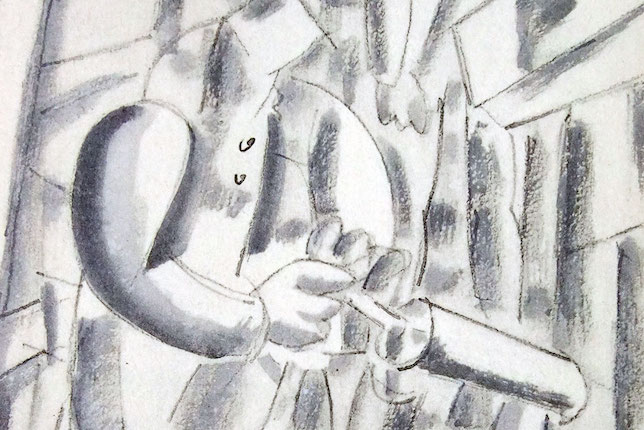

Fernand Léger’s oeuvre has largely become characterised by his abstraction of everyday forms into tubular metal elements. He combined attributes of the burgeoning Cubist art movement with a machine age aesthetic to produce a ‘Tubist’ style, as French art critic, Louis Vauxcelles refers to it. He skewed toward using volumes such as cones and cylinders as opposed to two-dimensional shapes, finding expression in curved, emphatically material forms.

Léger worked with a limited colour palette, which further drew attention to artistically engineered materiality as a key element of his paintings. He relied chiefly on form in evoking a metallic quality and conjured light as a means of defining that form. He shaded these curved metal cylinders into being, generating a reflective quality, which helps to distinguish their materiality.

Léger’s 1917 painting, ‘La Partie de Cartes’ demonstrates his tendency to overlay ordinary scenes with stylistic abstraction, using materiality as a tool to infuse deeper meaning into his work. He was conscripted into the First World War, where he worked as an engineer constructing trenches as well as a stretcher-bearer. These technical processes as well as his own experiences of war took form in his drawings, and later, became paintings.

‘La Partie de Cartes’, translated to the English, ‘Soldiers Playing Cards’, can be read as a commentary on the mechanism of war, as well as the mechanisation of those partaking in it. There is a distinctly inorganic materiality to the human forms in the piece. The ‘soldiers’ are not men so much as they are robots. The viewer perceives the formal elements of the body, enrobed in something more akin to sheet metal than muscle and skin. The soldiers become their armour, morphing into machines of war.

Léger would have been acutely aware of this hardening of humanity from his time ferrying wounded men from the battlefield, in whom he saw, first-hand, the suffering wrought by individuals as cogs in the war machine. Though, Léger was also struck by the super-human quality of those at war – “the crudeness, variety, humour and downright perfection of certain men around me, their precise sense of utilitarian reality and its application in the midst of the life-and-death drama we were in…”. So, there is a shadow side and a gleaming greatness to humanity, given form through the wartime experience. Through Léger’s development of materiality, we come to better grasp that dichotomy in the artist’s severe portrayal of modern beauty.

Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall

Frank Gehry’s architectural style has become one of the most identifiable of our time. Many associate his work with metal – swooping, curving, and crashing into harmonious exteriors the world over. His 2003 Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles is a spectacular example of this masterful application of materiality. The undulating metal-clad exterior is symbolic of the flow of music and the dynamism of the city in which it sits, a modern metropolis bursting with artistic impetus. Metal has long been representative of a futuristic sensibility, which offers a sleek, streamlined vehicle towards new possibilities. It’s a material that the project’s patrons insisted upon, championing this steely façade as a step into the future for the city.

Through its materiality, the Concert Hall engages light as a complementary medium. The manner in which light travels and changes throughout the day informs the performance of the building’s façade. At high noon, the exterior is aglow with the silver luminosity of day. By midnight, it’s dappled with the coloured lights of the city that rise up around it.

How a material interacts with light is a key defining factor. Is the medium rough and stippled like a brick, absorbing light and leaving rich colour and texture in its place? Or is it a gleaming sheet of metal which dances with the light, reflecting it back into the world with a titanium tint? Interestingly, this particular dance grew dangerous with the Concert Hall’s panels reflecting light much in the manner of a parabolic mirror. The concave forms concentrated beams of energy into nearby apartments and portions of pavement, creating hotspots of up to 60 °C.

The offending panels have since been sanded to dim their lustre, but the incidents serve as a striking testament to the importance of materiality in design. In this case, the symbolic value of the material trumped some functional considerations. Though ultimately, Gehry’s creation stands as an iconic piece of architecture that, while formally spellbinding, would not have delivered quite this future-facing star quality if it had been dressed up in anything but metal.

Tom Faulkner’s Hug Pendant

Left: Tom Faulkner’s Hug Pendant in Persian Silver with Florentine Gold | Right: Exterior detail of Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles; photographed by Joey Zanotti

Tom’s Hug Pendant is a beautifully articulated expression of materiality. There are echoes of Gehry’s work in the piece. We see hints of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in the Hug’s stark edges, in its furling form, and in its changeability as one circles the pendant. Though, perhaps more than anything, it’s the two works’ profound materiality that ties them together. We see it in how the medium is gracefully, precisely curved in the way only sheet metal can be manipulated. It comes through in the unique, steely gleam of the surfaces, which work with light from exterior and interior sources. Just as Gehry has created moments of reprieve in his armoured façade to welcome visitors, Tom has softened his design with a seam that opens, leaving a window into the light. The material hugs the light within before releasing it outwards into its environment.

Léger’s work takes on a similarly curvilinear quality, combining tubular volumes with cones that bear a resemblance to the Hug. They meld into soft, continuous forms through the artist’s application of light. There is a starkness to the metallic quality of the figures in ‘La Partie de Cartes’, but also a sense of awe in this burgeoning machine age potential. Tom’s design marries the two as a distinctly modern, sleek form of lighting that carries with it a softness and a warmth.

Metal is at the core of Tom’s furniture design practice. It’s a constant in his work but also in the creations of countless artists across disciplines and eras. It shows up as monumental works of future-facing architecture. Other times, it takes form as a painted harbinger of the stark yet energising possibilities of modernity. In all its forms, it plays a starring role in defining the aesthetic and symbolic quality of the piece, making an indelibly striking statement in the process.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn