The now infamous Bloomsbury Group was, at its essence, an informal collective of literary, philosophical, and artistic minds that came together in the early twentieth century. The group sprung up in London’s Bloomsbury, where most members were based. With an aversion to many of these characters’ strict Victorian upbringings, the Bloomsbury Group dove wholeheartedly into a culture of liberalism and fierce intellectual inquiry. This intoxicating atmosphere of open investigation and friendly debate produced some of the most important contributions to British Modernism. From the novels of Virginia Woolf to the economic treatises of John Maynard Keynes, to the painted works of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, the influence of their work was profound. Though, perhaps more pivotal was the reckless abandon with which they hurled themselves into life, embracing every whisp of pleasure they could get their hands around. This hedonistic bent found criticism in many circles, but there was an intention of joie de vivre and truthful expression at its roots. The outcomes may not have all been so decidedly positive, but their impetus was a noble pursuit of a life fiercely and fully lived.

The group began to take shape in earnest at the Gordon Square home of the Stephen siblings, Vanessa (Bell), Virginia (Woolf), Adrian, and Thoby. Vanessa began holding the ‘Friday Club’ in 1906 to provide an inspiring, collaborative environment for artists to work together. Thoby brought literary friends together for ‘Thursday Evenings’. The two gatherings were, in essence, something between a salon and a party. In tandem, they served as major points of genesis in the foundational ideas that would come to characterise the Bloomsbury Group.

The Bloomsbury members shared similar upbringings within relatively traditional upper-middleclass families. The free-wheeling, unconventional Bloomsbury lifestyle was a resolutely new direction for them, as they sought to shake off the shackles of their more clean-cut Victorian roots. Focus was pulled from politeness and a collective observance of conventions, and thrust upon personal relationships and individual pleasures. Bloomsbury figure, E. M. Forster goes as far as remarking that, “if I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country”. The group as an organisation (insofar as it can be dubbed as such) was not political in nature. Though, its members shared progressive beliefs on feminism, pacifism, and liberalism, contributing in no small part to the advancements of the ideas which surrounded these matters.

The Bloomsbury Group found a collective reverence for the works and personal philosophy of G. E. Moore. They put into action his notion that “one’s prime objects in life were love, the creation and enjoyment of aesthetic experience and the pursuit of knowledge”. They were armed with the moral convictions underpinning this idea, reflected by Moore’s concept of ‘intrinsic worth’ as separate from ‘instrumental value’. In other words, it’s not how we operate which defines us morally but rather, the impetus of that conduct. It’s easy to see how extra-marital affairs gained such pride of place within Bloomsbury: the judgement of any actions born out of the goodness of love was misplaced. What mattered was the presence of love as the morally commendable root of those actions. This ethos allowed, and indeed, often required, them to live and love outside the confines of traditional societal values. The coded customs of the old guard were supplanted with a rigorous pursuit of life lived fully for the pleasure of living, and “art for art’s sake”, as E. M. Forster put it.

One of the shining lights of the group is Virginia Woolf, now recognised as among history’s most important Modernist authors. She was a pioneer of the stream-of-consciousness writing style, transmuting her haphazard thought-patterns onto the page. She found inspiration in her romantic, often tempestuous, relationship with writer, Vita Sackville-West. One of Woolf’s most pioneering works, ‘Orlando’ forms a dizzying literary tribute to her long-time lover.

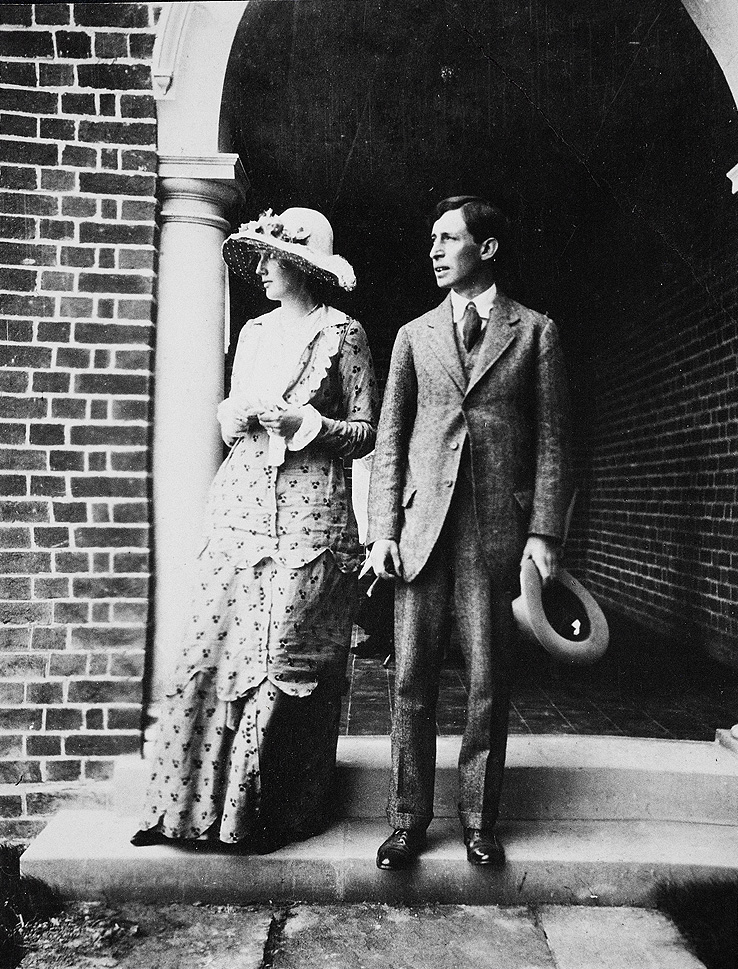

Left: Vita Sackville-West in 1916; photographed by E. O. Hoppé | Right: Virginia Woolf in 1902; photographed by George Charles Beresford

Woolf was plagued by mental illness throughout her life, which resulted in her institutionalisation on several occasions. The extreme highs and lows that she inhabited are palpable in her emotionally immersive work. In 1917, Virginia extended her literary reach beyond her own writing, founding the Hogarth Press alongside her husband, Leonard Woolf. They would publish T. S. Eliot, English translations of Freud, and many writers who made up the extended Bloomsbury family. Virginia’s sister, Vanessa Bell had a hand in the effort, designing many of the book jackets produced by the Hogarth Press.

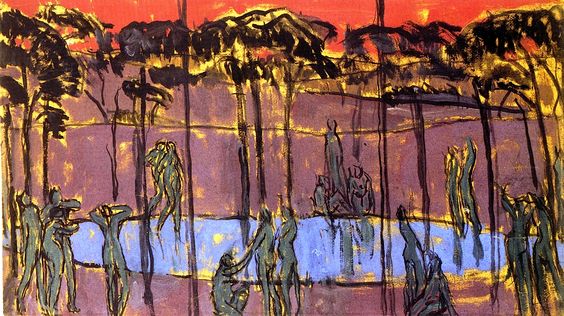

Vanessa Bell’s ‘Designs for a Screen: Figures by a Lake’ (1912)

Vanessa earned praise for her work as an artist as well as her contributions to design. Her work took inspiration from the post-Impressionist exhibitions arranged by Bloomsbury art critic, Roger Fry. Her painting also reflects stylistic influences from the Nabi artists who worked in late nineteenth century Paris to shift art towards abstraction and symbolism, laying groundwork for the emergence of Modernism. She embraced these artists’ bold treatment of form and vivacious colour palates, as exemplified by her 1912 work, ‘Designs for a Screen: Figures by a Lake’. These elements seeped into her paintings and design work, which was often underpinned by striking yet harmonious blocks of colour.

As was the case for most, if not all, Bloomsbury members, Vanessa’s work was shaped by her own personal relationships. Her husband, Clive Bell’s infatuation with the avant-garde artistic developments emerging from Paris filtered into Vanessa’s practice and invigorated the ideas which animated the Bloomsbury Group as a whole. Clive was an art critic who became associated with formalism, offering his own theory of ‘significant form’. He posited that the visual effect of an artwork carried greater importance than its content. In this line of thinking, the aesthetic value of art was to be its key defining factor.

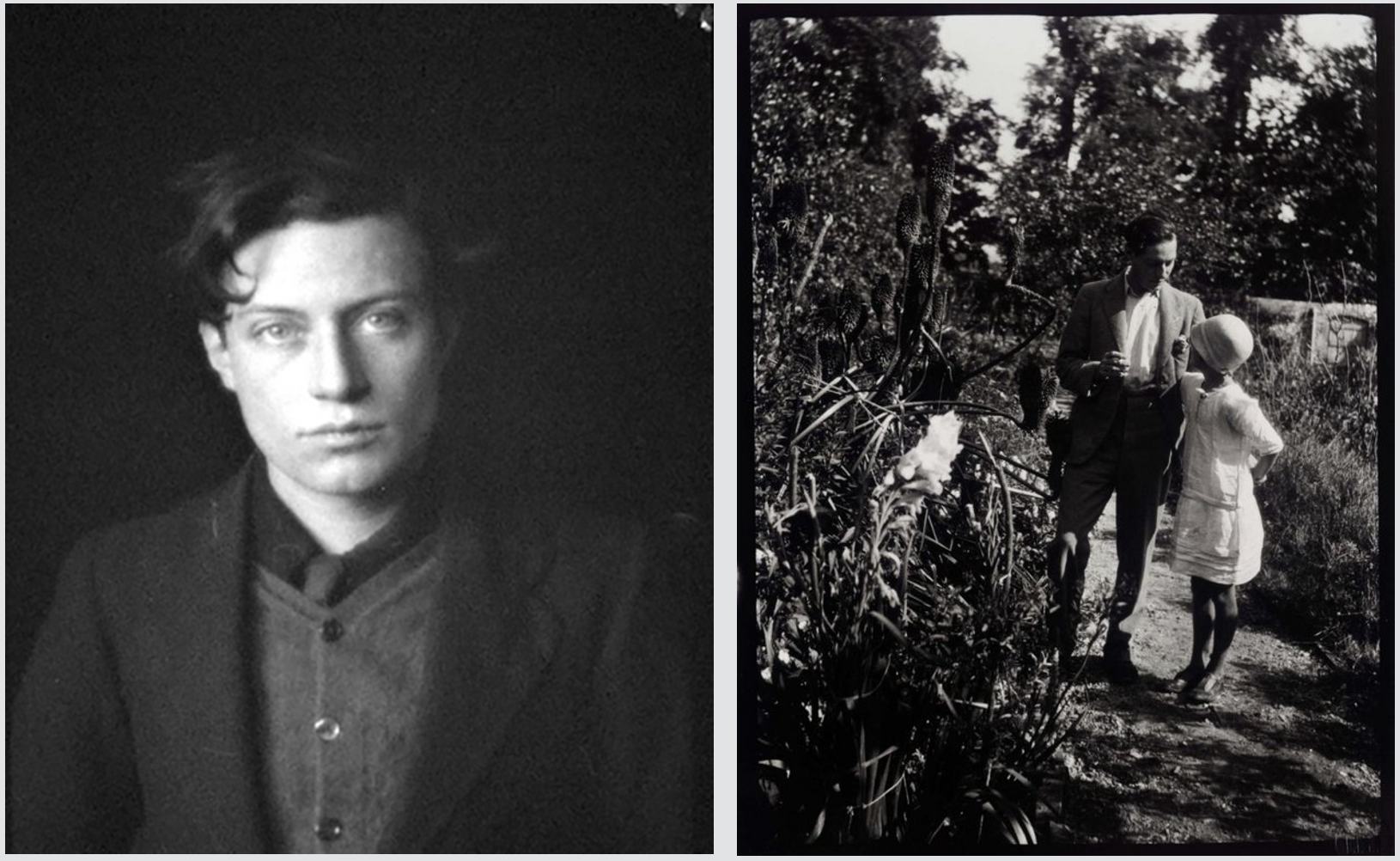

Left: Duncan Grant c. 1912; photographed by Alvin Langdon Coburn | Right: Duncan Grant and Angelica Bell in the garden of Charleston farmhouse in Sussex, 1927 © Tate

By the First World War, Clive and Vanessa had grown distant, and both leaned into their respective extra-marital relationships. Vanessa and Duncan Grant fostered a deep bond, which oscillated between a romance, a supportive friendship, and a creative partnership. The pair moved into Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex and, in 1918, decided to have a child together, naming her Angelica. She was welcomed by Clive and raised as his own daughter, alongside his and Vanessa’s two sons, Julian and Quentin. Angelica passed her youth unaware that Duncan was her biological father until just prior to her own wedding, when Vanessa concluded that it might be time to let her in on the news. Through it all, Clive and Vanessa never officially separated and maintained a friendly relationship, visiting one another regularly, spending holidays together, and paying family visits to Clive’s parents.

Duncan and Vanessa’s chemistry was all-encompassing, spilling into their creative work. In 1932, the pair was commissioned to create a dining set for Kenneth Clarke. They came up with the ‘Famous Women Dinner Service’, comprised of fifty plates emblazoned with the faces of noted women throughout history. They later worked together to create murals for the Berwick Church in Sussex from 1940 to 1942. The pair shared a distinctly special personal bond, which was coloured by Duncan’s intermittent trysts with the men who orbited the Bloomsbury Group. Unconventional though it may have been, it was a surprisingly stabilising relationship and the duo ended up laid to rest side-by-side at St Peter’s Church near their beloved Charleston Farmhouse.

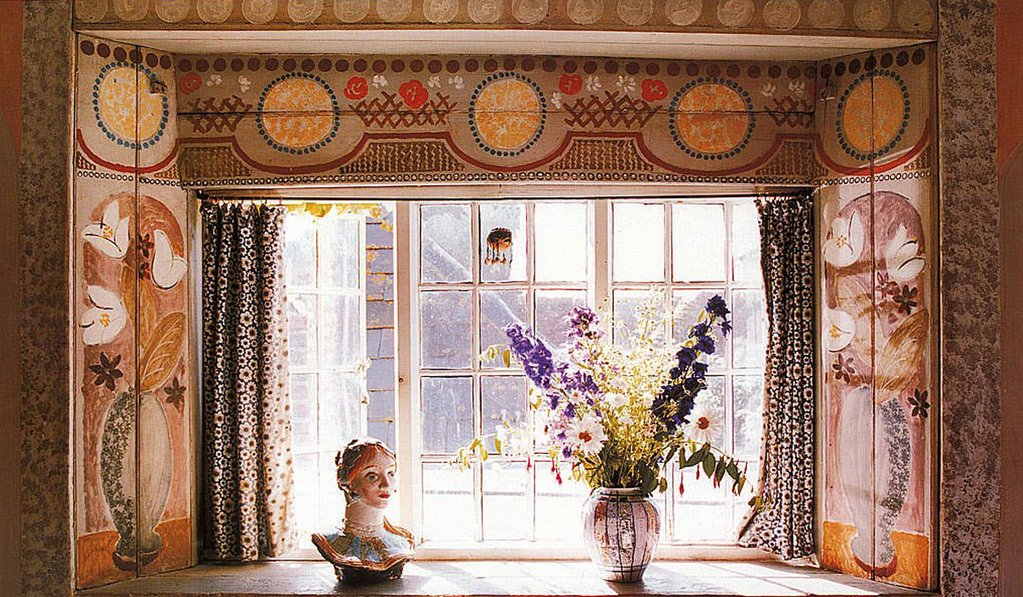

Charleston Farmhouse Interior

Charleston Farmhouse is a beautiful example of the melding of fine and decorative arts which Vanessa and Duncan orchestrated so seamlessly. Some of the country retreat’s most spectacular artworks border hearths and windows or are found splayed across walls. This new union of the arts was advanced by Britain’s eminent art critic, and fellow Bloomsbury member, Roger Fry. It’s with Roger that the aesthetic vernacular of the group found its clearest voice.

Roger met a pivotal force to his artistic paradigm when he first encountered the works of Paul Cézanne. He shifted his focus to shining a light on the Parisian avant-garde style which would come to play a key role in defining his – and, indeed, Britain’s – artistic taste. This is when he moved away from the Old Masters to support the Modern artistic vanguard. To this end, Roger established the Omega Workshops, which gained notoriety as a champion of emerging artists. Omega even played host to Vanessa Bell’s first solo exhibition in 1916, which helped to introduce decorative arts to the greater public, casting them in a new light and blurring the lines between what had been considered the ‘high’ and ‘low’ arts. In the words of Kenneth Clarke, Fry was “incomparably the greatest influence on taste since Ruskin …In so far as taste can be changed by one man, it was changed by Roger Fry”.

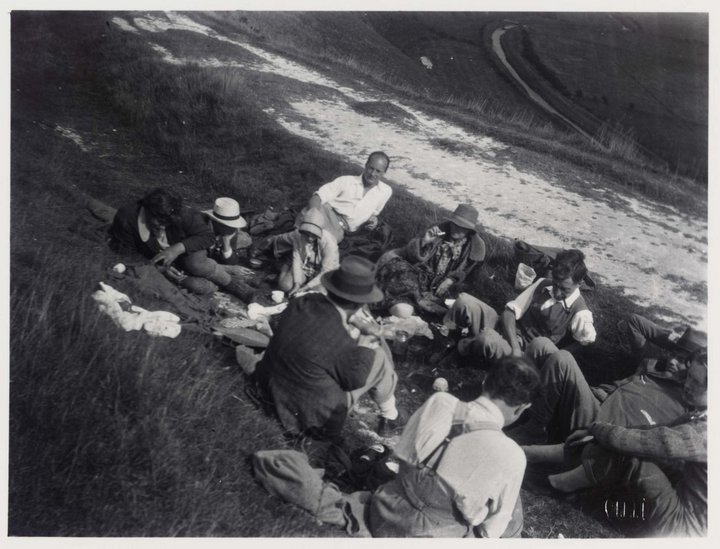

Bloomsbury Group picnic at High and Over, Sussex © Tate

The influence of the Bloomsbury Group is owed in equal parts to the great literary minds, economic thinkers, aesthetic philosophers, and artists who animated it. Their contributions took on manifold forms, though they were united by a common commitment to challenging the modes of thought which had calcified in Britain, breaking them apart to give way to a new, Modern consciousness. They did so with a sense of abandonment to the pleasures of existence, fostering a spirit of passionate engagement with life, from the deepest of its valleys to the highest of its peaks.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn

Title Photo: Duncan Grant, ‘Bathing’, 1911 © Tate