Mark Rothko (centre right), Peter Lanyon (top left), Terry Frost (right), and friends having lunch at Paul Feiler’s House in Kerris, Cornwall in 1959

There is a felt sense of place in the art of Modern St Ives. There are traces of the humble British ways which built the seaside town, but also of the grand, fresh ideas which came in on itinerant artists like barnacles on the hull. The siren call of this simple fishing village both attracted and evoked pioneering creativity on an international scale. There is a clear exchange of ideas which took place between the Modernist style emerging from St Ives and that of its American and Continental counterparts. The product is a slippery amalgamative style that carries with it the mark of this place perched at the tip of Britain’s Cornish tendril.

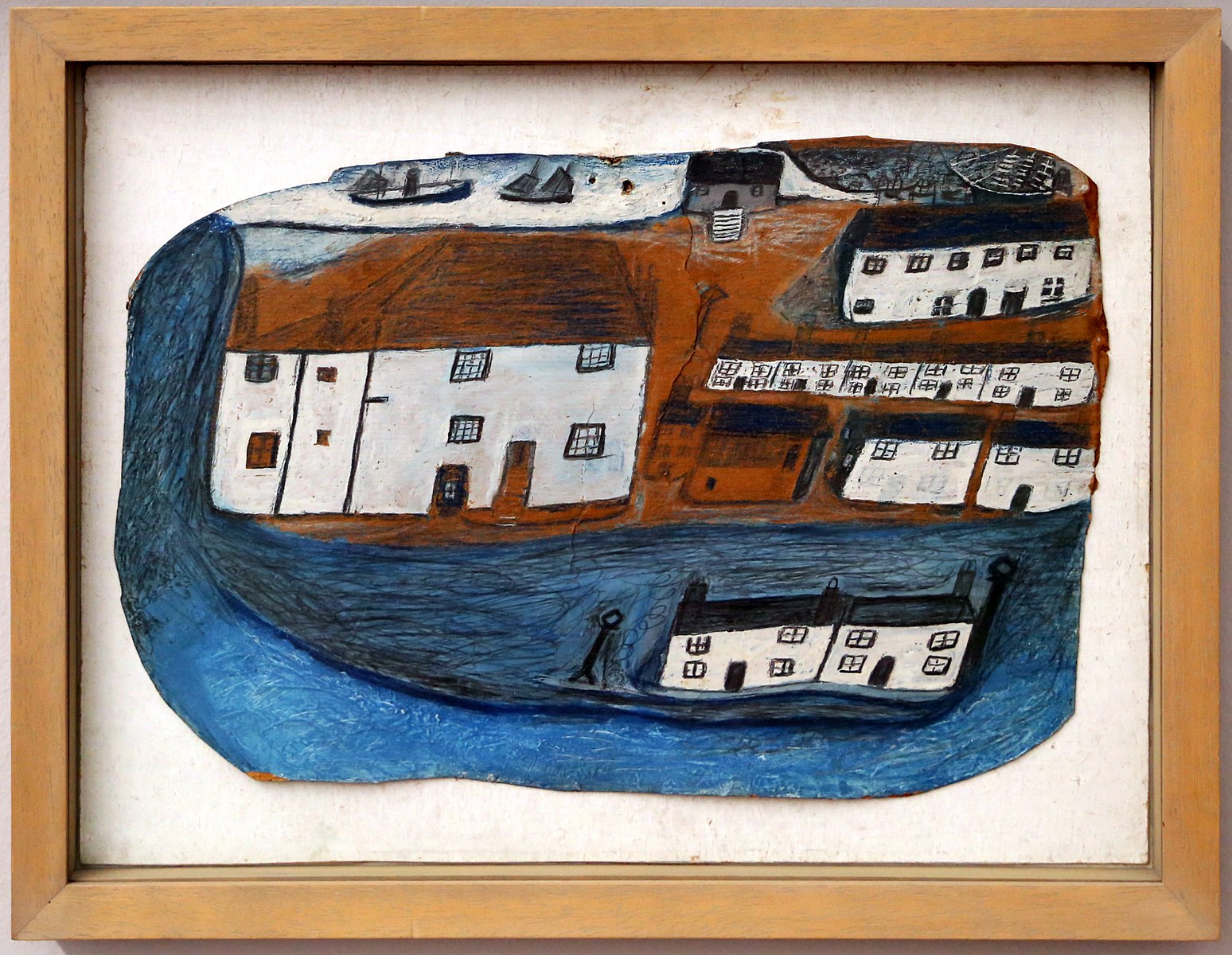

Alfred Wallis

St Ives has its roots in the sea, and Alfred Wallis is a shining product of the invigorating, yet unforgiving life that came with those origins. He was a mariner, first and foremost. He began his days training as a basketmaker in the late nineteenth century, developing a hand in craft that would later serve him as an artist. Though, the bulk of his working life took place upon schooners traversing the North Atlantic between Penzance and Newfoundland. If wasn’t until his wife died that he turned his attention to painting “for company” more than anything else, as he recounted to late Tate curator, Jim Ede. He came to it at the age of seventy, with many years at sea to draw inspiration from. These were these scenes that flowed from his memory onto scraps of cardboard that he salvaged for the sake of economy.

These works of Wallis’s are fine examples of Naive Art. He was entirely self-taught and simply painted fragments from his mind’s eye. Wallis’s approach to scale leaves us clues as to what stood out as important to him in each scene. The larger elements, perspectivally out of tune within space, betray a sense of gravitas and sentimental magnitude within the artist’s mind. The schooners he knew so well sweep across his scenes, dwarfing shore-side houses and nearly outshining the seas they sit upon. There is a sense of dynamism in Wallis’s slanting edifices that speak to a life lived racing through the waves at full tilt. These are some of the unique qualities of his work that struck Ben Nicholson when he came to St Ives, establishing an artist colony alongside Christopher Wood. Nicholson was spellbound, encapsulating Wallis’s art as “something that has grown out of the Cornish seas and earth and which will endure”. And so it has.

Ben Nicholson

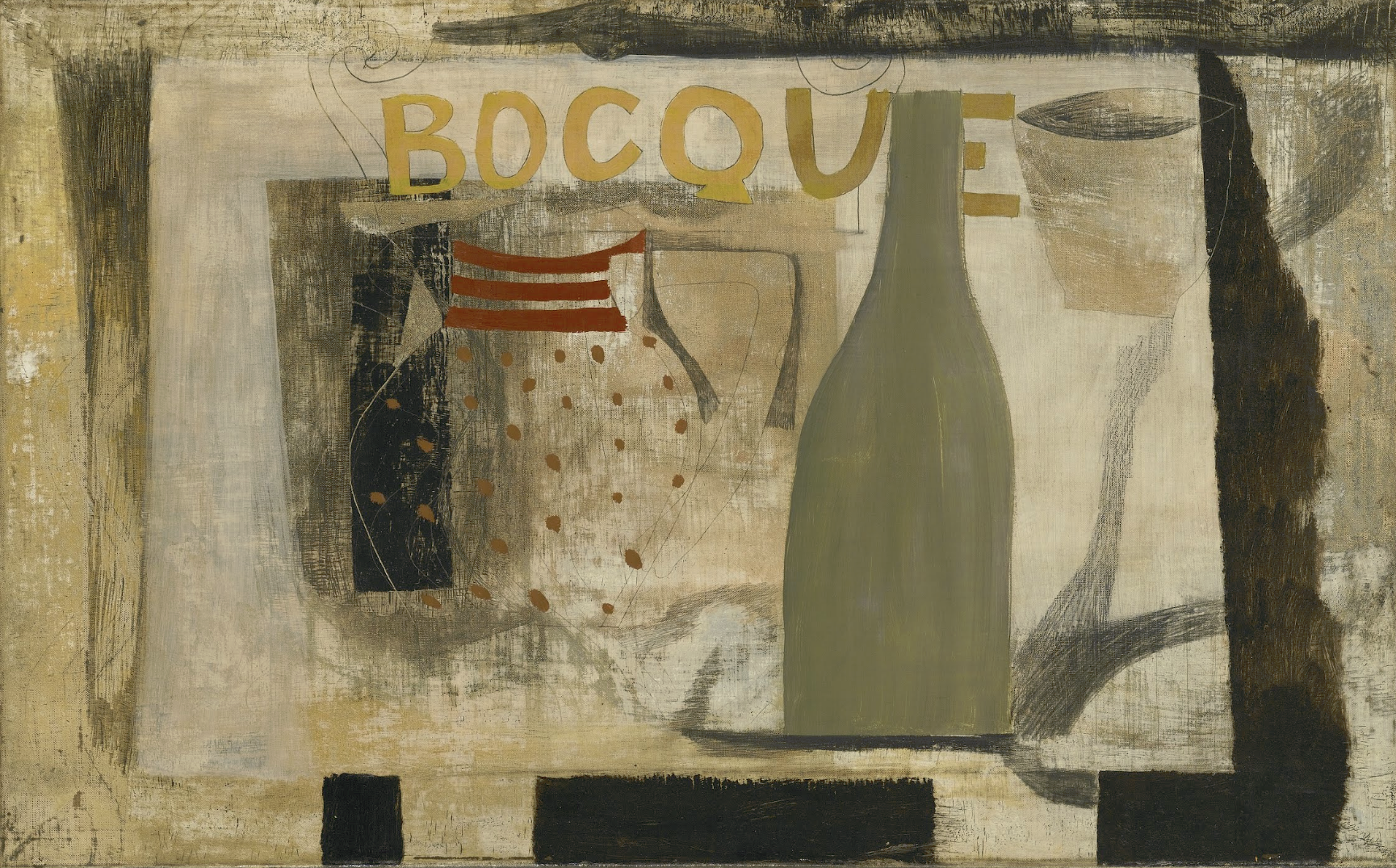

Ben Nicholson’s visual vernacular beautifully represents of the artistic character of St Ives. For his subjects, he turned often to still-lifes and schematically executed pelagic landscapes. From these simple, quotidian delights, he spun true Modern masterpieces. He benefitted from a formal art education at the Slade School in London, though he drew a great deal of inspiration from the beauty of his everyday pursuits, famously favouring the abstract formality of billiard balls gliding across green baize over the work of academic masters. His own style was influenced not only by the work of his wife, Barbara Hepworth, but also by the couple’s Continental sojourns. They travelled extensively, visiting the studios of Pablo Picasso, Jean Arp, and Constantin Brancusi in Paris. They even got to know Georges Braque and Piet Mondrian along the way. Striking elements of Braque’s style, in particular, appear to have seeped into Nicholson’s work. Even a cursory glance at his 1932 work, ‘Bocque’ reveals similarities to Braques oeuvre. His flattening and overlaying of still-life subjects, alongside the introduction of fragmentary text and a use of mousy, muted hues throughout indicate an adaptation of European Modernist sensibilities.

From his arrival in 1928, Ben Nicholson quickly became a stalwart of the St Ives artistic community. He was based in a beachfront studio at Porthmeor, which played host to many of his artistic friends over the years. Wilhelmina Barns-Graham worked out of the studio, Francis Bacon took up residence there for a time, and Terry Frost was based just next door. His orbit, in St Ives and beyond, was formidable, as was his contribution to Modern Art on a global scale.

Barbara Hepworth

Left: Barbara Hepworth’s ‘River Form’ (1965) (foreground) and ‘Figure’ (‘Achaen’) (1959) (background); photographed by puffin11k | Right: Barbara Hepworth’s ‘Three Standing Forms’ (1965)

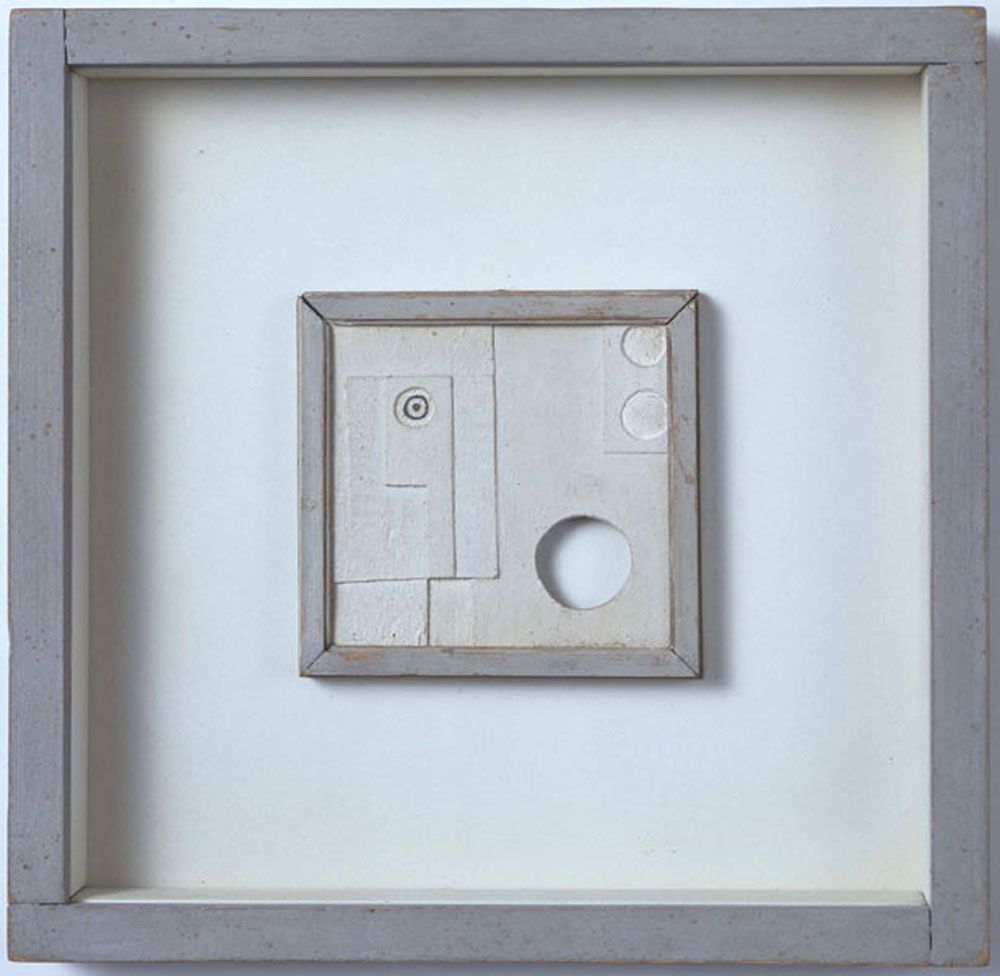

Barbara Hepworth was born into the dramatic beauty of Yorkshire, though it wasn’t long before her artistic passions spurred her further afield. She studied at London’s prestigious Royal College of Art before travelling to Florence on an arts scholarship. It was here that she learned the art of carving marble and met her first husband, John Skeaping. Their marriage, however, was all but swept away when Hepworth crossed paths with Ben Nicholson. Nicholson was also, rather inconveniently, married at the time. Though, the pair swiftly took steps to sever ties with their first spouses and entered into what would become an immensely creative union based in St Ives. Hepworth and Nicholson found a sense of support between them that allowed each artist to go further than they’d gone before. There’s evidence of an exchange of ideas in Nicholson’s 1934 work, ‘Relief’, where he appears to have borrowed geometric elements of Hepworth’s distinctive artistic vernacular. The pair brought this cooperative spirit abroad, where they engaged with the lustrous new systems of thought emanating from Paris and encountered a fresh American sensibility.

Hepworth and Nicholson became involved in the Abstract-Création artistic movement, alongside Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Wolfgang Paalen, among others. The group were champions of abstraction in art as a path to the deep truths they sought to access through their work. Hepworth was invigorated by these new ideas, returning home with a motivation to marry her insights on abstraction and surrealism with the unique aesthetic environment of British art. She also engaged deeply with Constructivism alongside Russian artist and thinker, Naum Gabo, who had come to be an influential figure in St Ives at the time.

Hepworth had long been acquainted with artists closer to her own Yorkshire origins, like Henry Moore, in whom she found a friendly competitor. There was a give and take between the artists, who often worked with form in similar ways, prizing amorphous, organic shapes, often perforated by circular porthole-like features. These are the familiar forms we’ve come to love in her work, born of the rocky shores of St Ives. Hepworth took full advantage of this inspiring environment, finding the perfect base in her now famous, Trewyn Studio. Hepworth remarks, “Finding Trewyn Studio was sort of magic. Here was a studio, a yard, and garden where I could work in open air and space.”. Her art sits at the confluence of so many great artistic movements, but carries with it a clear and constant hum of its immersion in the energising, windswept landscape of St Ives.

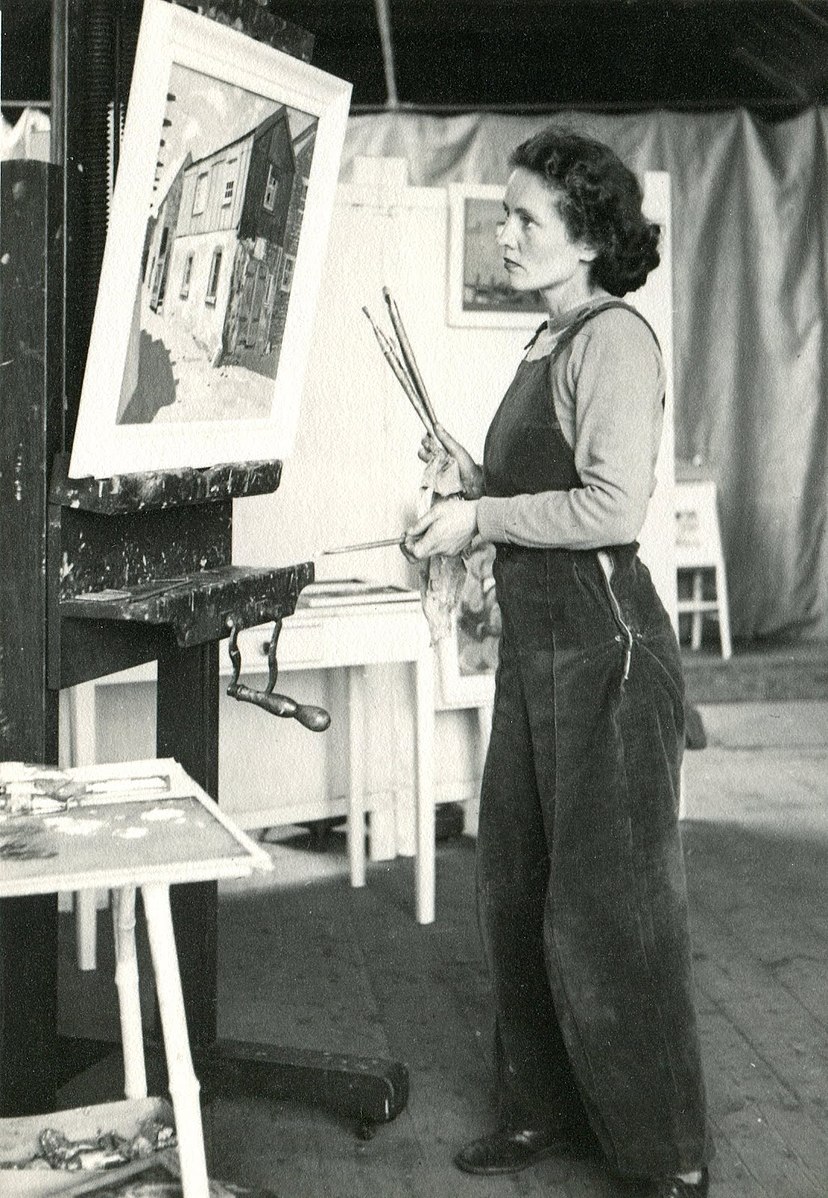

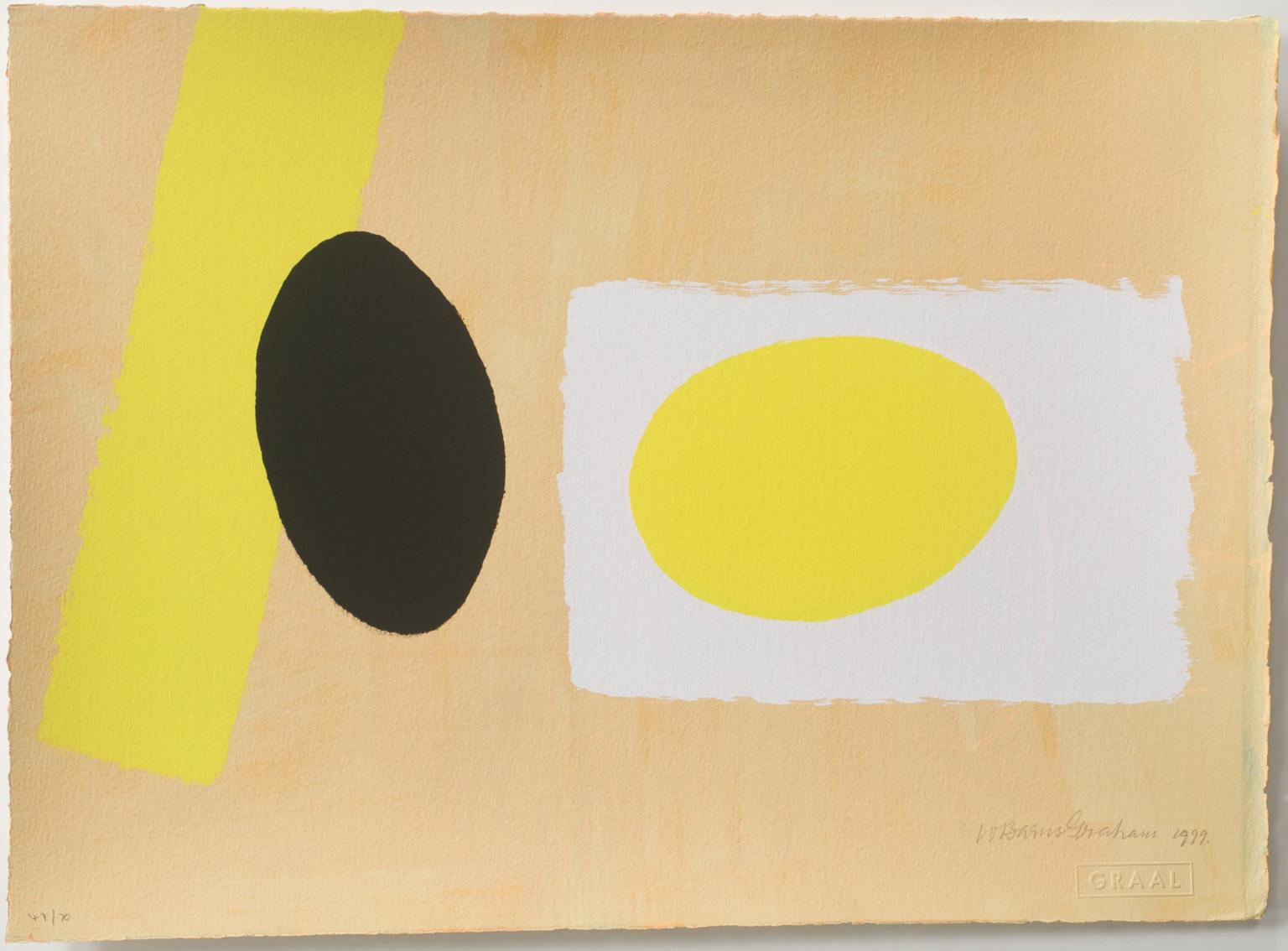

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham was yet another transplant in the St Ives artistic community, arriving in 1940 having grown up in St Andrews, Scotland. This was a time of great artistic influx for the Cornish town as the Second World War set in. Barns-Graham made her mark on the community as a founding member of the Penwith Society of Arts. The group was established by a collection of artists who sought to break away from the more conservative St Ives School. This dynamic, forward-thinking ethos rings through in her work, which was led by a spirit of curiosity and a refusal to settle or be pinned down.

Barns-Graham’s art teeters on the border between landscape and abstraction. She took an intriguing approach to perspective and space, largely informed by her interaction with Noam Gabo, who was interested in the concept of stereometry at the time. Stereometry encouraged the consideration of formal subjects from all perspectives, including the internal view. This idea echoes the Cubist fascination with capturing three-dimensional forms in their entirety, within the two-dimensional bounds of painting.

Barns-Graham’s work then progressed into more abstract, geometric realms, as she enthusiastically continued to follow where her artistic curiosity led. She relates her appetite for creative exploration, noting, “In my paintings I want to express the joy and importance of colour, texture, energy and vibrancy, with an awareness of space and construction. A celebration of life – taking risks so creating the unexpected.”. It was in this spirit that Barns-Graham created endlessly innovative, insatiably mutable art that was both a poetic expression of her philosophy for living, and a truly special visual catalogue of the ethos of Modern St Ives.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn