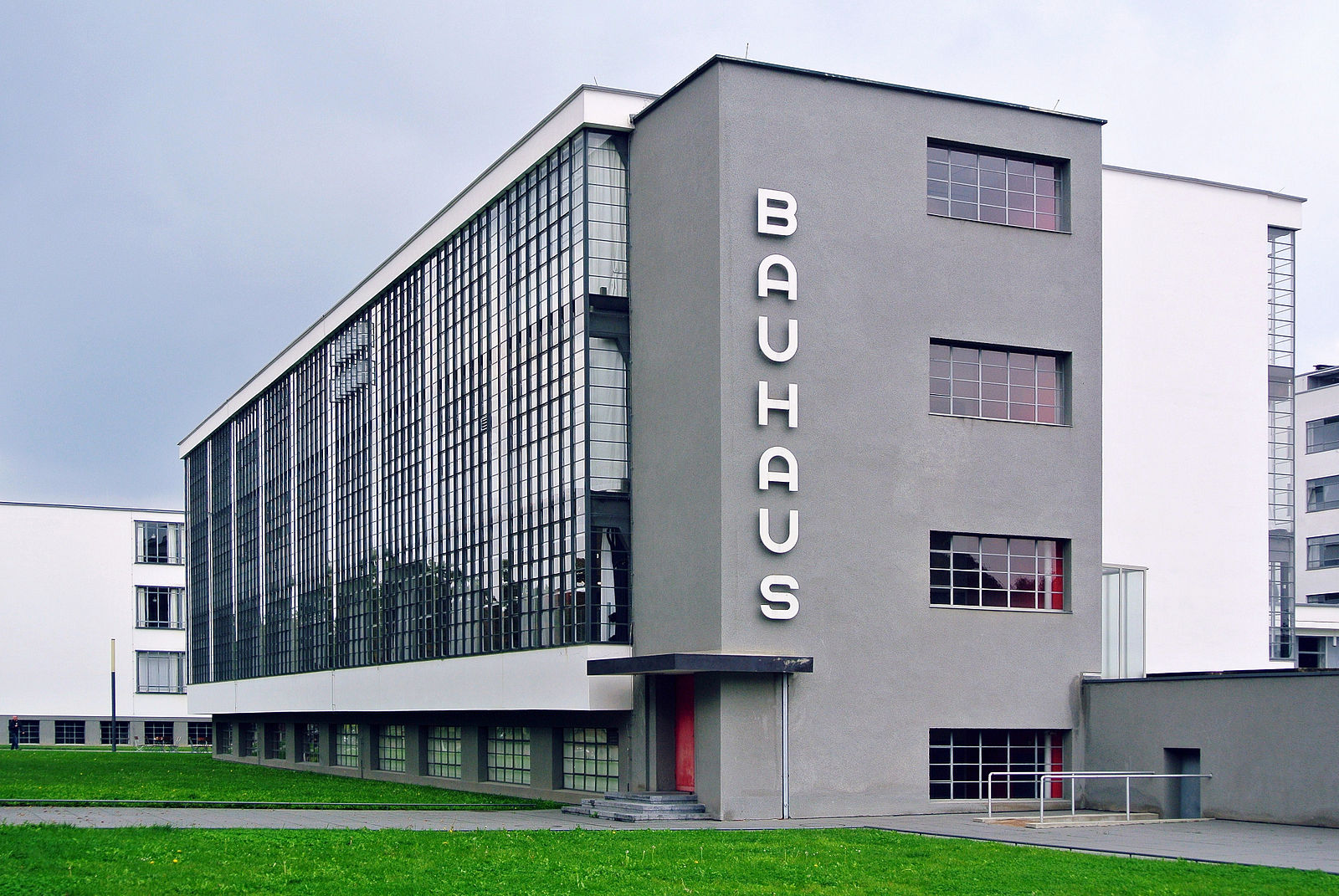

Technically speaking, the Bauhaus was a German art school, which ran from 1919 to 1933 – but really, it’s drastically more than that. From the school grew the movement, which spanned across creative disciplines and, ultimately, eras. It started with Walter Gropius in Weimar, though, leadership changed hands over the years, leaving Hannes Meyer at the helm for a time, followed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Each shift brought changes in creative focus and new political leanings, but the school’s central drive remained constant. At the core of the Bauhaus was a respect for the artistic vision of the individual, which was then introduced to a mass-scale production model. It was a delicate, yet intrinsically necessary balance. The aim was to infuse aesthetic delight into the everyday, the functional, the overlooked. As such, a grand production apparatus was key, yet it was vital that the carefully considered artistry that went into each design was preserved.

Bauhaus Dessau, designed by Walter Gropius (1926); photographed by Spyrosdrakopoulos

The German, Bauhaus translates literally to “building house” in English. Here, applied arts and fine arts were brought into the same arena and assigned equal weight. At its heart, the Bauhaus was envisaged as a vehicle for convening all the arts, under the banner of Gesamtkunstwerk, or “comprehensive artwork”. They made their presence felt across furniture design, product design, architecture, and graphic design, drawing artists from these various disciplines together under one roof.

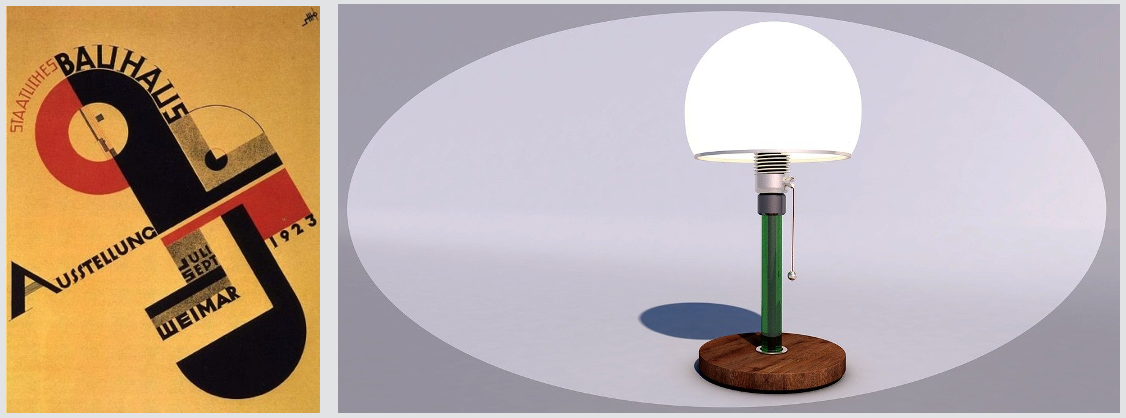

Left: Joost Schmidt’s Bauhaus Ausstellung (1923) poster for a Bauhaus exhibition; Right: Wilhem Wagenfeld and Carl Jakob Jucker’s Table Lamp (1924)

Artists like Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, and Wassily Kandinsky all taught within the Bauhaus school, infusing their ideals into all manner of creative expressions. Marcel Breuer, whose prime interests lay in architecture, immortalised this cross-discipline influence in the form of his Wassily Chair, after the great Russian painter-cum-teacher. There is a similar use of line between Breuer and Kandinsky, as seen between the former’s Wassily Chair and the latter’s painting, Inner Alliance. Both artists’ lines follow geometrically led, carefully measured paths, establishing layers of intersection along the way.

Left: Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair (1929); photographed by Jeff Belmonte; Right: Wassily Kandinsky’s Inner Alliance (1929); photographed by Dudva

The Bauhaus style is expressed through simple, geometric design for the sake of function above all else. Any superfluous ornamentation is avoided in favour of original treatment of form. Bauhaus architecture is an interesting embodiment of this approach, with its block-like composition, as seen in The Bauhaus Museum in Tel Aviv designed by Shlomo Gepstein in 1934. The building is part of The White City, which has earned UNESCO World Heritage Site status as the highest concentration of Bauhaus buildings in the world.

The Bauhaus Museum in Tel Aviv, designed by Shlomo Gepstein; photographed by BergA

This boom in Bauhaus architecture within Israel followed the dissolution of the school in Germany. Those running the school made the decision to close under pressure from the Nazi regime, who pinpointed the group as a powerful locus of communist intellectual activity. Though, this was far from the end of the Bauhaus. As its leaders and their pupils scattered across the globe, they carried the torch with them and continued to develop the ideas which powered the school. Ultimately, if anything, this broadened the influence of the Bauhaus, reinvigorating its expressions as it was freed from a physical space, morphing into its immortal incarnation as a conceptual approach to creation. You can dispel a schoolhouse, but you can’t destroy the ideas which ultimately defined it – and, indeed, continue to animate it.

Moholy-Nagy went on to establish a new American home for this ideology with The New Bauhaus in Chicago, which exists to this day as the IIT Institute of Design. Here, Moholy-Nagy was galvanised by the belief that in creating art, we are also making ourselves. What we design, develops who we are as well as how we live. So, the Bauhaus spirit continues to colour us on a societal level, seeping into contemporary creation and those at its helm. The influence is felt in some of Tom Faulkner’s furniture designs. The bold simplicity and intersecting linear elements of his Berlin Dining Chair speak to the Bauhaus admiration of visually clean, function-forward objects. Tom’s Apollo Side Table shares this Bauhaus bent, with its purely geometric, block-like form.

Left: Tom Faulkner’s Berlin Dining Chair in Bronze with Midori Green Leather; Right: Tom Faulkner’s Apollo Side Table in Polished Stainless Steel with Glass

The Bauhaus, rather unfairly, has taken on something of an austere, exacting reputation in the collective hindsight. Although, this was very much not the case. Their creativity spilled over into their frequent themed parties, which are said to have been legendary. They were, in many ways before their time, with a student body made up of equal parts men and women. There was a restraint in ornamentation but certainly not in the way those in the school thought freely and lived wholeheartedly. They were, as it turns out, a whole lot of fun. And so, we can count our blessings that the vivacious, original Bauhaus sensibility lives on across the globe, infusing dignity and beauty into the everyday.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn

Feature Photo: Wassily Kandinsky’s Composition 8 (1923); photographed by Gandalf’s Gallery