The glass house has become an icon of Modern architecture, representing a move towards a certain purity of form, galvanised by distinctly mechanistic materials. At their core these innovative designs were, however, machines for living, built to serve as homes, enfolding and elevating the daily rhythms of domestic life. They’re simultaneously true architectural marvels as well as containers for the lives and spirits of those for whom they were built. There’s a very human story behind each of these pioneering places, from Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Edith Farnsworth House to Philip Johnson’s Glass House. We’ve collected a few of our favourites to delve a little deeper into life behind the glass walls.

Crystal Palace

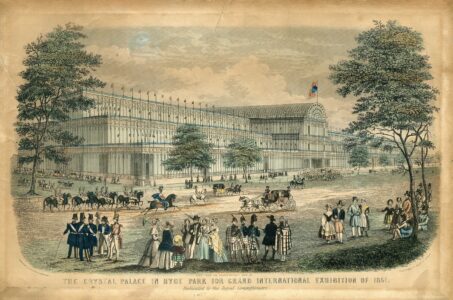

To start with a touch of historical context, we go back to the Industrial Age to have a look at London’s ephemeral Crystal Palace. It was a period that saw architects move towards novel, utilitarian materials like steel and glass. Crystal Palace is a remarkable expression of this collective shift towards a Modern aesthetic.

Crystal Palace was designed by Joseph Paxton and Owen Jones to be built within Hyde Park as the site of the Great Exhibition in 1851. It played host to this display of innovate technological achievements, echoing the spirit of mechanical progress in its spindly steel structure and crystalline walls. It was an artifact in and of itself, which put on display not only an exhibition of technological curiosities, but also the patrons who came to see them. Onlookers could gaze in through the glass panes and watch the masses as they milled about, creating a new architectural dynamic.

Following the exhibition, Crystal Palace was packed up and moved to Sydenham. It sat high on a hill surrounded by park land, until it went down in flames in 1936. Though it still very much holds a landmark place in the architectural character of the age, sending ripples through time to inform designs like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Edith Farnsworth house 100 years in the future.

Edith Farnsworth House by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Edith Farnsworth House is a true emblem of Modern architecture. The long and low country hideaway was designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with direction from the owner, Dr Edith Farnsworth, who went on to live there for two decades following its completion in 1951. It was originally conceived of as a weekend retreat, though she became progressively drawn to the house as the pair worked out the functional kinks, like the leaks so common in Modern flat-roofed homes, for example.

A bit of errant water was, unfortunately, the least of their problems throughout the construction phase. Disagreements around cost brought Farnsworth and Mies van der Rohe to court, nearly driving them to abandon the project entirely. We can be thankful they stuck with it, producing this streamlined template for so many glass homes to come.

The white steel and crystal-clear glass set the place off against its environment, nestled within the trees of Plano, Illinois. The pared-back approach produced something of a viewing platform for its natural surroundings, creating space for Farnsworth to meditate on all manner of cultural curiosities. She threw herself into her pursuits, supporting pioneering works of design – so much so that the name of her home was recently changed to pay homage to this doyenne of the arts. The National Trust for Historic Preservation added the ‘Edith’ to honour her contribution to the creation of the landmark house, as well as to Modern architecture on a grander scale. It’s a welcome amendment to the story of this starkly beautiful place that’s inspired decades of innovation in its wake.

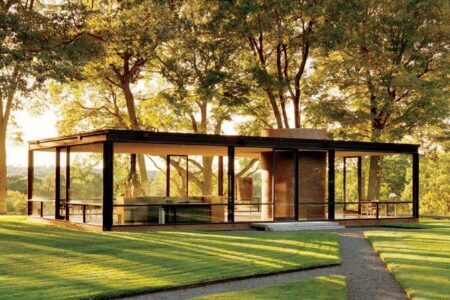

The Glass House by Philip Johnson

Philip Johnson’s Glass House holds a special place for us. Tom has long been influenced by the geometric charcoal lines and chrome-tinted interiors of this landmark home. He even made the pilgrimage to see it in 2018. So, it came as an honour to donate a selection of our glass-topped Lily Cocktail Tables for the auction at the Glass House’s recent summer party. It’s a pleasure to be a part of this architectural icon’s story and to help support its enduring legacy.

This emphatically minimalist home came to completion in 1949 in New Canaan, Connecticut. The architect designed the home for himself, tailoring every detail as a conduit for domestic life as he hoped to live it. For 58 years, the Glass House was a beloved weekend retreat of Johnson and his partner, David Whitney, who curated their art collection and led the charge on designing the landscape they were so immersed in. The manicured outdoor spaces were inspired by a painting of theirs, Nicolas Poussin’s 1648 work, ‘The Funeral of Phocion’, echoing the sweeping sensation of the work and integrating copses of trees as natural ‘vestibules’.

The duo initially lived between the Glass House and the nearby brick guest house, before deciding the clean-cut glass space was better suited to entertaining. Johnson was an early adopter of this Modern wave of mechanistic design, building the house in a small selection of carefully chosen materials. The framework took shape in charcoal painted steel, sitting atop a brick floor with a cylindrical brick bathroom extending up to the ceiling. They furnished the space with Modern pieces that echoed the spirit of the house, like chairs by Mies van der Rohe and sculptural works by Donald Judd. The landscape formed their living environment, Johnson once quipping, ‘I have very expensive wallpaper’. The Glass House is a container for living, but one that feels liberatingly permeable. It’s a piece of pioneering architecture intrinsically in-tune with the natural world as it fuses with Modern human creativity to produce something entirely new.

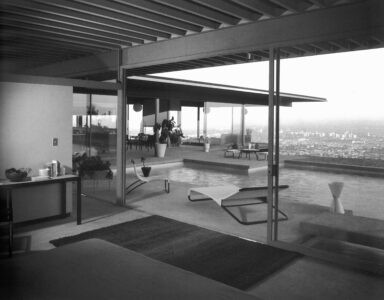

Stahl House by Pierre Koenig

Peering out over the Hollywood Hills is the iconic Stahl House, designed by Pierre Koenig. It was an experimental design, also going by the name of Case Study House #22, completed in 1960. It was built as a home to Carlotta and Buck Stahl’s family, though it’s since become more famous for its onscreen appearances. The couple would rent the house out for film shoots, taking a room at the Chateau Marmont just beneath so as to get out of the crew’s hair. A careful eye will spot the hilltop house in various movies and music videos – an adaptation even appears in the video game, Grand Theft Auto. It’s a piece of architecture truly ingrained in the Southern Californian cultural consciousness.

The house itself is almost entirely glassed in, its façade being the only exception. Great swathes of glass form its outer walls, allowing for the 270-degree view of the city below which Buck Stahl envisioned. It’s a format that allows inhabitants to feel truly immersed in the landscape, looking out along clear lines of sight and allowing the architecture itself to fall away around them. It takes on an L-shaped footprint around the pool, which forms the heart of the home, extending almost all the way up to the glass walls of the house.

Famed photographer, Julius Schulman captured a photograph of the house, which turned the place into something of a posterchild for modern Los Angeles architecture. Though from the beginning, it was intended as a family home, first and foremost. It was an ambitious project, though it worked well for parents, children, and friends. With an open-plan, convivial living arrangement and an outdoor-oriented format, it was home to many family memories before it entered the ranks of monuments to American architecture. There’s a soul to this place that exists in the space, as opposed to on the screen, giving it lasting character alongside its daring design.

Text by Annabel Colterjohn